Planning Chicago

Everyone plans. Businesses contemplate markets and products, social service agencies seek to improve service to their clients, workers think about retirement, politicians calculate their chances for reelection. In the language of urban history and policy, however, “planning” refers to efforts to shape the physical form and distribution of activities within a city. The objects of planning are sites and systems—the neighborhoods and places within which we carry on our lives and the networks that link the parts of a metropolitan area into a functioning whole. Planning shaped everything from Pullman and Hyde Park to the Chicago park system and the web of highways that knit together the metropolitan region.

Planners divide into two groups. By far the most common are the “moneymakers”—the city builders (and rebuilders) of the private sector and private markets. From single individuals and households to the developers of entire new communities, they try to meet existing demand and support social patterns by intensifying the use of land. They put houses on vacant lots, subdivisions and industrial parks on cornfields, office towers on the sites of low-rise buildings. They work within the competitive framework of the real-estate market, but the city they create is unified by common assumptions. In each generation, city builders have created vernacular neighborhoods and business districts that reflect prevailing tastes and market forces, whether Greater Grand Crossing and Austin in the nineteenth century, the Bungalow Belt of the early twentieth century, or the Edge Cities of the late twentieth century.

Less common but also influential are the “community makers” who are the focus of this essay. These government agencies, civic organizations, and owner-developers work with the conscious goal of altering social relationships and making “better” places through the planning of urban sites and systems. Some have concentrated on creating specific urban environments that are more socially harmonious and personally fulfilling than the market usually has provided. Other civic-minded community makers have searched for ways to make the city and its surrounding region function more efficiently. The story of planning in Chicago is thus the story of special places built from the ground up, such as Riverside or Park Forest; it is the story of places self-consciously rebuilt, such as Lake Meadows or the University of Illinois at Chicago; and it is the story of comprehensively designed support systems, such as parks and highways.

Community planning in Chicago has unfolded in four overlapping stages—eras in which particular planning concerns took center stage within the larger context of market-driven growth. In the first half of the nineteenth century, government actions constructed a spatial framework for the new city. From the 1850s to the early years of the twentieth century, the city and its environs were the location for a sequence of privately built, comprehensively planned, and idealized communities. From the later 1880s through the 1920s, the city experienced an unusual era when public and private interests coalesced around efforts to integrate the sprawling metropolis. And since the 1930s, metropolitan Chicago has witnessed gradual erosion and fragmentation of that civic vision as the goals of planning have become more specialized or limited.

Chicago’s planning history offers a lesson that can be generalized to other American cities: efficiency is an easier goal than equity. Residents have found it relatively easy to agree and act on community needs that invite engineering solutions, for it has been possible to argue convincingly that canals, roads, sewers, and parks serve the entire population. Chicagoans have been less ambitious and less successful in shaping ideal communities that combine physical quality with social purpose. They have tried repeatedly to improve on the typical products of the real-estate market, but their experiments have faced often intractable issues of class and race. Success has usually required planning for narrowly defined segments of the middle class, while planning for socially inclusive communities at any large scale has built social conflict into the community fabric.

Drawing the Grid

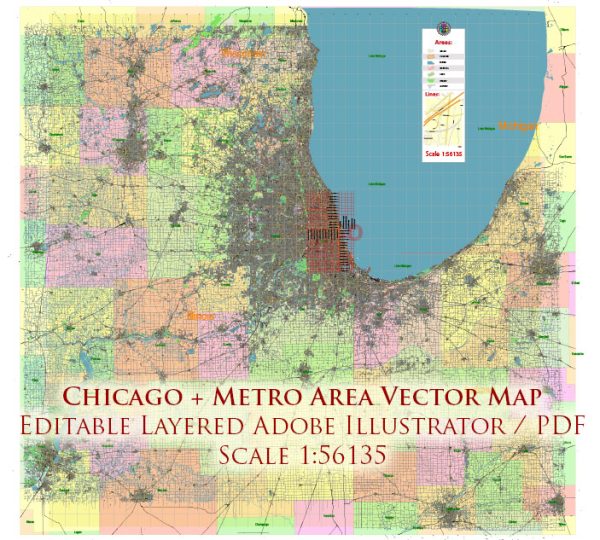

Chicago got its start from the federal and state governments. Fort Dearborn (1803) was a federal military outpost that helped the new nation assert its claim to the Northwest and protected American traders. Its location helped the commissioners in charge of the state-built Illinois & Michigan Canal choose the mouth of the Chicago River for its northern terminus. The small grid of streets that the commissioners platted in 1830 at the junction of the north and south branches of the river set the street pattern that private developers began to extend as early as 1834. Chicago’s growth was also framed by the square-mile grid of the federal land survey, whose section lines would become major arterial streets as the city grew (Halsted Street, Chicago Avenue, and Roosevelt Road).

Local government also began to assume responsibility for basic infrastructure. Charter amendments in 1837 gave the city the power to directly supervise public works. The state in 1851 authorized a public commission to build a water system with city funds and bond issues; in 1855 it added a sewerage commission. In 1861 a Board of Public Works took over management of water supply, sewerage, drainage, and streets. In the ensuing decades, water mains, sewers, and paved streets followed population outward into Cook County in a repeated process of catch-up (only developers of the most upscale suburbs commonly provide such necessary services).

Perfect Places

Chicagoans in the second half of the nineteenth century built a set of influential communities that embodied social purpose. As the city’s new rail lines fanned outward over marshes and prairies and opened a seeming infinity of sites for community making, developers hurried to subdivide and profit from new neighborhoods and towns. Most efforts were simple grids with poorly graded streets and small lots. A few developments on the fringe of the industrializing city, however, pushed the envelope of the market beyond the simple provision of shelter and accessibility. Expressing Chicago’s early exuberance and confidence, their goals were sometimes lofty—in some cases to allow harmonious relations between urban residents and their landscape, in other cases to promote compatible relations between workers and employers.

Chicago’s planned residential communities along commuter railroad lines were models for other nineteenth-century suburbs that sprang up outside Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. Their spacious design and attention to natural settings gave them continuing influence on community planners well into the twentieth century. In contrast, Chicago’s industrial utopias moved quickly from admired experiments to examples of problems to avoid.

Following the initial examples of Llewellyn Park outside New York and Glendale near Cincinnati, Chicago’s first planned suburbs represented attempts to think through and express a better relationship between people, their city, and their landscape. In the 1850s, Evanston (1853) and the “pleasant woodland town” of Lake Forest (1856) matched universities to upscale housing (and the strict morality of prohibition in Evanston). Lake Forest and especially Riverside (1869) offered convenient access to the advantages of the city while being built with the natural landscape in mind. Upper-middle-class families who moved to the new towns enjoyed clean air, good water, picturesquely curving streets, large lots, parks, and public gathering places—all with a direct rail commute to the center of Chicago. They were escapes from the urban energy of the emerging downtown and close-in neighborhoods, but not from the city-region as an economic machine. Their residents gained quiet evenings and Sunday strolls along the lakeshore or the Des Plaines River, but they made their money oiling the gears of commerce.

Industrialist George Pullman intended his new town to serve the best interests of factory workers and factory production. Built on undeveloped land 10 miles south of the city, the town of Pullman offered new housing within walking distance of huge new factories. Like other company towns, its corporation was a paternalistic landlord that sought to manage the lives of its workers. Like more expensive suburbs, it also offered a version of the suburban ideal—clean air and water, an escape from flimsy speculative housing, and the opportunity for women to focus on home and family while men brought home a living wage. But the reform agenda of the 1880s collapsed during the bitter Pullman Strike of 1894; within a decade Pullman was another industrial neighborhood with good housing stock, not a suburban experiment for the working class.

Harvey (1891), another new industrial satellite on the South Side of the city, was a less comprehensive version of Pullman. Having learned about some of the problems of a single-company town, lumber king Turlington Harvey laid out a city to which he invited factory owners and workers who shared the values of evangelical Protestantism. For a few brief years before the depression of the 1890s, Harvey flourished as a temperance town. Without the distractions of saloons or gambling, sober native-born workers and industrialists could share an interest in hard work, appearances by evangelist Ira Sankey, and lectures by Susan B. Anthony. In 1895, however, with Turlington Harvey’s business in disarray, residents voted the town “wet.” The vote ended the experiment with what historian James Gilbert has called a “religious, countercultural city,” although the town’s schools and social services benefited from benevolent industrialists into the new century.

By the time the United States Steel Company laid out the new city of Gary in 1906, industrial corporations were wary of mixing social mission with worker housing. Designed for a population of 200,000, Gary had an ordinary street grid and privately owned housing. It gave over the lakefront to factories, railroads, and harbor. For the rest of the site, U.S. Steel acted like a giant tract developer with few overtones of paternalism, although title to lots did not transfer until houses were completed.

As Gary suggests, the “perfect communities” of the twentieth century have often been cities for industry rather than people. Chicago entrepreneurs in the 1890s invented the “industrial district.” The Union Stock Yard and the Chicago Junction Railroad organized the Central District in 1890 and began to market its facilities in 1905. The company prepared land, assured rail service, put in utilities, graded streets, built standardized factory buildings, and leased space for factories and warehouses. The Central Manufacturing District (which soon controlled several separate sites), the Clearing Industrial District, and many others were subdivisions for industry. The thousands of industrial parks that dot the landscape of late-twentieth-century America are their direct heirs.

Metropolitan Planning

In the decades around the turn of the century, a widely shared metropolitan vision coalesced around the planning of systems to integrate the sprawling Chicago region. New York and Chicago epitomized the urban crisis of fin de siècle America, whose institutions seemed to be overwhelmed by waves of European immigration, increasing polarization of wealth, and the sheer complexity and congestion of the giant city. These challenges of headlong metropolitan growth called forth similar responses in both cities. Some Americans reacted with sweeping utopian or dystopian visions of the national future. Others searched for practical technological fixes such as electric lighting, improved sanitation, or electric streetcars and subways. Still others constructed ameliorative institutions such as settlement houses and began to lay the foundations of a modern welfare state with the social and economic reforms of Progressivism. And a significant minority worked to systematize the future growth of their cities, consolidating separate local governments into vast regional cities and developing regional plans for the extension of public services.

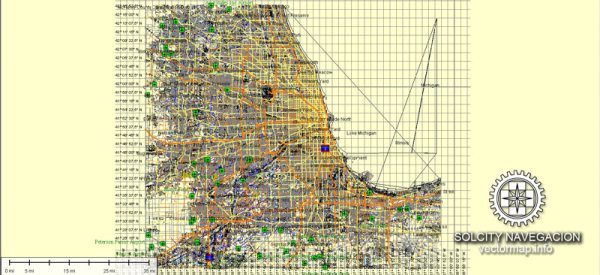

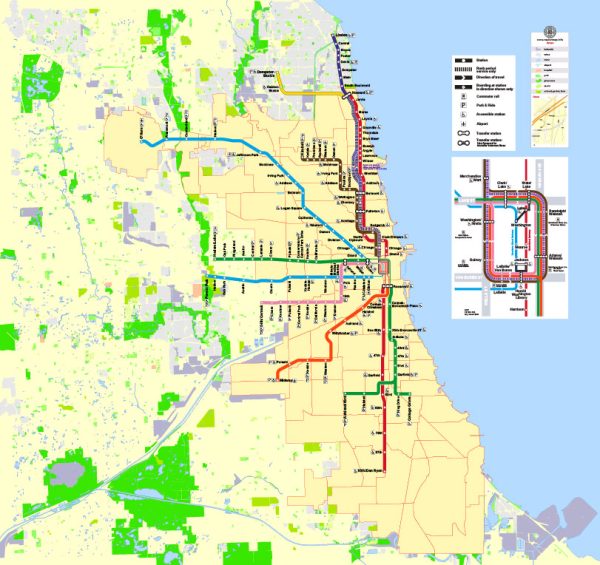

This story began in Chicago with the park system of the late nineteenth century. Although separate South, West, and Lincoln Park commissions (1869) served the three geographic divisions of the city, their investments and improvements worked together as a unified whole. Large semipastoral parks in the zone of the fastest residential growth allowed the poor and middle classes to enjoy temporary respite from the city. Broad boulevards connected the parks in a great chain from Lincoln Park to Jackson Park.

The annexation of 1889 tripled the area of the city; it took in established suburban communities and vast tracts of undeveloped land and set the stage for large public expenditures for water supply and sanitation. The Sanitary District of Chicago (1889) covered 185 square miles; its impressive regional accomplishment was construction of the Sanitary and Ship Canal (1900) and the reversal of the Chicago River to carry the city’s waste into the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers. Annexation also paved the way for a metropolitan vision that achieved full expression in Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett’s Plan of Chicago of 1909. Promoted by a civic-minded business elite and widely embraced by middle-class Chicagoans, the “ Burnham Plan ” was an effort to frame the market (and the work of city builders) with a regional infrastructure of rationalized railroads, new highways, and regional parks to anticipate population growth. The plan knit downtown and neighborhoods, city and suburbs and surroundings, to a distance of 60 miles. It was to be implemented with public investments that would order and constrain the private market. The plan took the regional booster vision of the nineteenth century and transformed it into a concrete form and format for shaping a vast but functional cityscape.

Economically comprehensive as well as spatially unifying, the plan envisioned a Chicago that located management functions, production, and transportation in their most appropriate places. It assumed that the city would continue to be the fountainhead of industrial employment. Its vision of mutually supportive interests of business leaders and the mass of Chicago workers was naive in light of such failures as Pullman and the city’s continuing record of labor-management conflict. However, it still offers a conceptual contrast to the decades after World War II, when urban renewal and downtown redevelopment planned for the transformation of the economic base from manufacturing to services rather than the enhancement of the industrial economy.

From the early 1900s into the 1920s, Chicago benefited from a “civic moment” when business interest and civic interest seemed to converge, at least in the minds of privileged Chicagoans. Middle-class women as well as men took active roles in the discussion. Groups such as the Women’s City Club battled for an accessible park system and for public access to the waterfront. Although such organizations often opposed narrow economic development schemes floated by businessmen, they were important participants in the same planning discourse about the best ways to implement the vision of Burnham and Bennett.

The commercial-civic elite mounted a vigorous campaign to put the Burnham Plan into action. The city established a unique City Plan Commission—a miniature city parliament of 328 businessmen, politicians, and civic leaders—to monitor and promote implementation. Advocates tirelessly preached the gospel of urban efficiency with newspaper and magazine stories (575 in 1912 alone), illustrated lectures, a motion picture, and Wacker’s Manual of the Plan of Chicago, a summary text that introduced the Burnham Plan to tens of thousands of Chicago schoolchildren.

Chicagoans acted in accord with many of Burnham’s prescriptions. The city acquired lakefront land for Grant Park, a stately open space to set off and contrast with the growing skyline. Creation of the Cook County Forest Preserve system implemented another set of recommendations. So did the extension of Roosevelt Road, improvement of terminals for railroad freight and passengers, movement of harbor facilities to Lake Calumet, and widening of North Michigan Avenue to allow expansion of the downtown office core.

As growth moved beyond the city limits, civic leaders in 1923 organized the semipublic Chicago Regional Planning Association. This effort to keep alive the planning vision of the 1910s was a forum for the voluntary coordination of local government plans outside the direct control of Chicago. Involving municipalities from three states, it had substantial success in coordinating park expansion and highways. However, the growing scale of the metropolitan area also introduced the erosive problem of suburban independence and competition for growth that would dominate regional planning in the United States in remaining decades of the century.

The Burnham Plan was certainly not perfect—it spoke to social issues indirectly at best—but it did place the question of good urban form at the center of the public agenda and held up Chicago as a model for wide-ranging thought about metropolitan futures. A publication entitled Chicago’s World-Wide Influence (1913) trumpeted the importance of Chicago planning. Burnham and Bennett had tried out their ideas in San Francisco and followed with consulting work in other cities. The Plan of Chicago was also a template for more “practical” comprehensive planning in the 1920s.

Ironically, the Plan of Chicago and its implementation provided the context for New York to retake the lead in urban planning. The adoption of zoning in Chicago (1923) followed New York’s pioneering ordinance of 1916. The Regional Plan for New York (1929) not only dealt with the same issues as had Burnham and Bennett but added more careful attention to the patterns of land use. By the 1930s, the Northeast had captured leadership in planning thought with Harvard University’s graduate planning program, the reform-minded Regional Planning Association of America, the grand public works program of Robert Moses, and experimental communities such as Radburn, New Jersey, and Greenbelt, Maryland. The New York World’s Fair of 1939 highlighted urban issues in a way that Chicago’s Century of Progress (1933) had not. Even The City (1939), the classic documentary film on issues of urban growth, used New England, Pittsburgh, New York, and Greenbelt to illustrate its ideas—not Michigan Avenue or Riverside.

1930–2000: Picking up the Pieces

Since the 1920s, the civic ideal has eroded in the face of racial conflict, suburban self-sufficiency, industrial transition, and the daunting complexity of a huge metropolitan region. Like every other large American metropolis, Chicago has fragmented by race and place. At the same time, urban planning as a field of work began to splinter into poorly connected subfields. Advocates of public housing worked in the 1920s and 1930s for specific state and federal legislation. Proponents of improved social services became social workers and bureaucrats of the incipient welfare state. Engineers and builders of physical infrastructure concentrated on adapting a rail-based circulation system to automobiles, as with Chicago’s Wacker Drive, Congress Expressway, and hundreds of miles of newly paved or widened thoroughfares. In Chicago and elsewhere, New Deal work relief programs reinforced the transmutation of comprehensive planning into a set of public works projects. City planners were left to effect incremental changes in private land uses by administering zoning regulations.

Chicagoans returned to the intentional creation of “better” communities with the help of the federal government after World War II. The Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954, the bases for an urban renewal program lasting until 1974, were intended as federal-local partnerships to rescue blighted city districts with exemplary reconstruction. But the politics of planning required that new or newly improved neighborhoods be homogeneous communities for single races or classes. This generation of neighborhood planning found it possible to bridge the chasms of class or race, but not both. The results were not necessarily bad, but they were neither as comprehensive nor as socially integrative as planning idealists might have hoped.

A central postwar imperative was how to keep white Chicagoans on the South Side in a time of heavy black migration and ghetto expansion. The city in the 1950s used urban renewal to clear low-rent real estate, attract new investment in middle-class housing, and buffer large civic institutions. A key example was the city’s partnership with Michael Reese Hospital and Illinois Institute of Technology to create the new neighborhoods of Lake Meadows and Prairie Shores. High-rise apartments integrated middle-class whites and middle-class African Americans while displacing an economically diversified black neighborhood. The city and the University of Chicago worked together on a similar makeover of Hyde Park that preserved the university and a university-oriented neighborhood while building economic fences against lower-income African Americans. Federal funds also financed arrays of public housing towers, such as the Robert Taylor Homes, to hold black Chicagoans within the established ghetto.

Oak Park since the 1960s has offered an alternative approach to middle-class integration. Oak Park residents have used social engineering rather than land redevelopment to manage integration and harmonize some of the tensions of race and place. Working through private organization rather than municipal government, Oak Parkers have directly faced the problem of racial balance and quotas, marketing their town to white families and selected black families and steering other blacks to alternative communities.

The planned suburb of Park Forest (1948) tried to be inclusive by class (at least the range of the middle class). In so doing, however, it was solving a problem of the last century rather than directly addressing the issues of race and suburban isolation. The Park Forest plat reflected the best of midcentury suburban design, using superblocks to reduce the impact of automobiles and assembling the blocks into neighborhood units with neighborhood parks and schools. It also mixed single-family homes and two-story garden apartments so that upward mobility was possible within the same community. Park Forest has nonetheless gained increasing racial variety, emerging in the 1980s as another example of successful integration.

Park Forest, like Riverside, Evanston, and Pullman in the previous century, also assumed that men and women operated in separate spheres. Such communities turned inward on home and neighborhood for women and children while opening out to the workplace for men. This social vision would prove fragile as social customs changed and a majority of American women entered the workforce by the 1970s.

Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood offers a twist on the Park Forest story. Efforts to replicate the Hyde Park experience of racial integration failed in the 1960s and 1970s, in part because of the contrast between middle-class whites and working-class blacks. Instead, it has gained as a broadly based African American neighborhood with the help of development efforts orchestrated by the community-oriented South Shore Bank (now ShoreBank).

In a less progressive variation on the Oak Park and South Shore examples, the private sector has increasingly controlled downtown redevelopment in the interests of business corporations and their professional and managerial employees. Through the 1960s, redevelopment initiative remained with the city because urban renewal put local governments in control of land acquisition. The University of Illinois campus in Chicago was built on lands acquired through urban renewal. In a variation on the Hyde Park / University of Chicago story, it transformed tracts originally intended for replacement housing into a pioneering public campus. As federal urban renewal funds dried up with the Housing and Community Development Act (1974) and the Reagan administration, however, the public sector lost most of its capacity to act directly. Efforts to leverage mixed-use development have met with success outside the Loop but left a gaping hole in the center of downtown during the 1990s.

Planning for regional systems, in contrast, has been more successful. Infrastructure planners can fall back on the rhetoric of technically sound proposals and sidestep direct confrontation with racial conflict. The Chicago Regional Plan Association issued Planning for the Region of Chicago in 1956. The Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission (NIPC) began work for a six-county region in 1957; it has issued and updated regional plans for water, open space, recreation, and land development. The 1962 plan of the Chicago Area Transportation Study (CATS) was a national model for transportation demand forecasting. CATS (now a federally recognized transportation planning organization) and NIPC have had the practical success of framing a regional road/rail system that reflects Burnham and Bennett’s ideas and has kept the vast metropolis together.

Nevertheless, regional growth frameworks cannot themselves stem intraregional competition for jobs and upper-income residents. Mayor Richard M. Daley might admonish his suburban counterparts in 1997 that “we have to think of mass transit as a regional issue,” point proudly to the continuing importance of downtown Chicago jobs, and convene meetings to discuss regional cooperation. Only the federal courts, however, have been able to override local isolationism on issues such as low-income housing.

Conclusion

Chicago’s nineteenth-century planners assumed that good communities reflected and protected homogeneity—homogeneity of class as in Riverside and Lake Forest, homogeneity of culture as in Harvey. As exemplified in Pullman, their efforts foundered when faced with the differing values and expectations of workers and capitalists, native-born Chicagoans and immigrants, Protestants and Roman Catholics.

In the civic moment of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, business interest and “civic” interest converged around the physical redesign of the metropolis. Much of the private sector was self-consciously public in rhetoric and often in reality. Middle-class women as well as men shared a vision of a reformed city that was implicitly assimilationist. The well-oiled economic machinery of the metropolis would have a place for everyone; improved housing and public services would help to integrate newcomers into the social fabric.

Even as the imposing Plan of Chicago was being so vigorously promoted, however, Chicago’s growing black population was posing a challenge that lay outside the intellectual framework of physical planning. The congratulatory report Ten Years Work of the Chicago Plan Commission (1920) made no reference to the bloody race riot of the previous year. In the second half of the century, planning fractured into technical specialties and efforts to improve pieces of the metropolis—downtown, historic districts, new suburbs, and the occasional integrated neighborhood. In a time when everyone acknowledges the economic unity of city regions, the continuing challenge is to reinvigorate the civic-mindedness that has served Chicago well in the past and to craft political alliances and civic institutions to support physical efficiency and social equity across the entire metropolitan area.

Source: http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/972.html

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS