The history of railroads and road systems in Chicago, Illinois, is closely tied to the city’s growth and development as a major transportation hub in the United States.

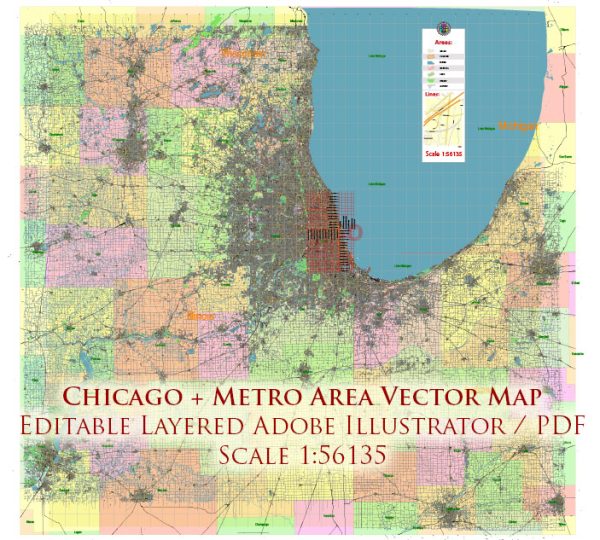

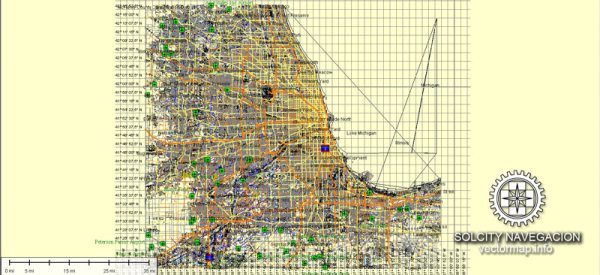

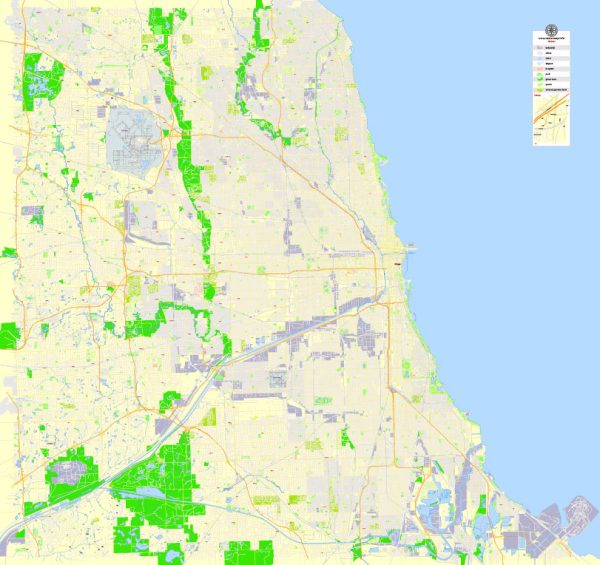

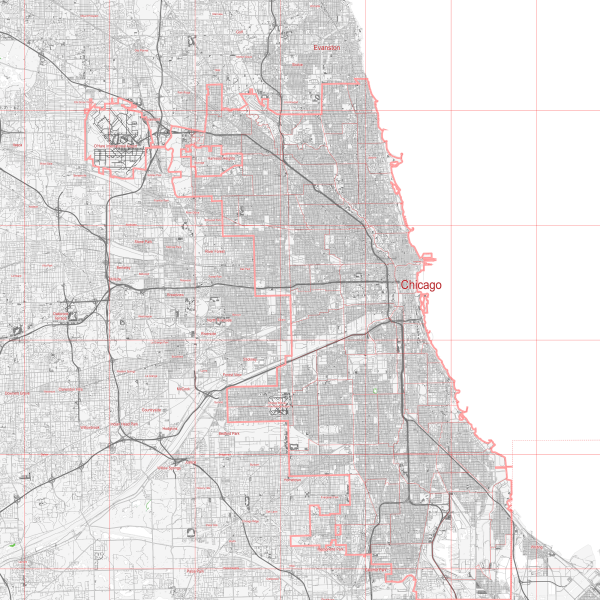

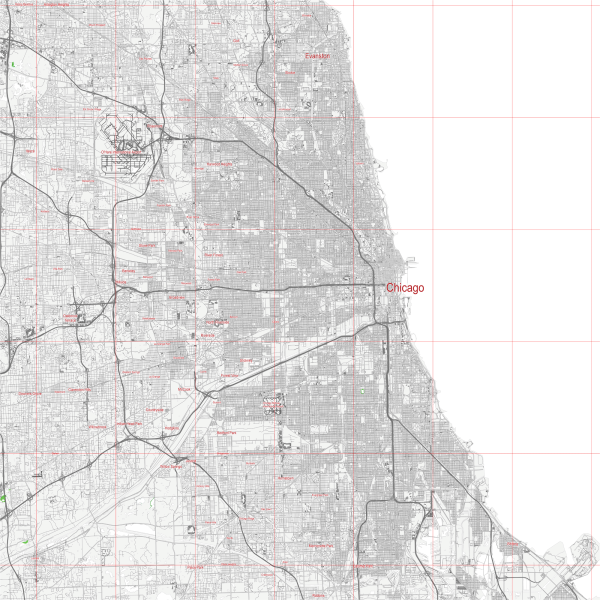

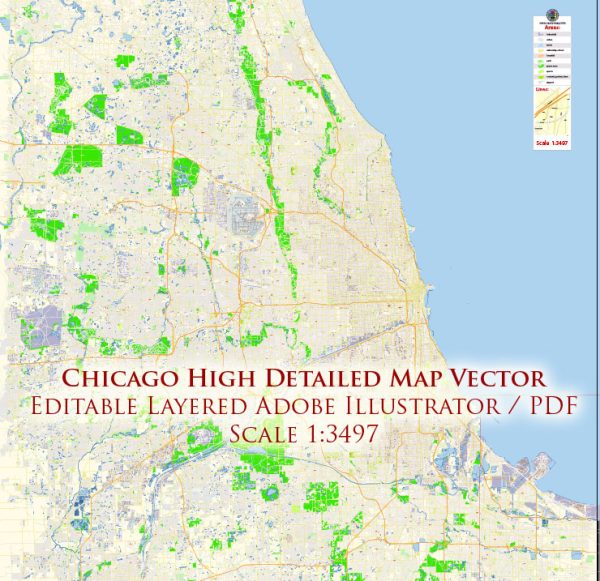

Vectormap.Net provide you with the most accurate and up-to-date vector maps in Adobe Illustrator, PDF and other formats, designed for editing and printing. Please read the vector map descriptions carefully.

Here is a detailed overview:

Early Transportation:

- 1830s-1840s: Chicago’s early growth was fueled by its strategic location at the southwestern tip of Lake Michigan. The city’s first transportation links were water-based, with early settlers relying on Lake Michigan and the Chicago River for shipping and trade.

Railroad Expansion:

- 1848: The Galena and Chicago Union Railroad, the first railroad in Chicago, was completed. It connected Chicago with the lead mines in Galena, Illinois, and marked the beginning of Chicago’s role as a transportation hub.

- 1850s: Several other railroads, including the Illinois Central and the Chicago and Northwestern, were established, connecting Chicago to various parts of the Midwest and beyond. This rapid expansion made Chicago a central point for the convergence of multiple rail lines.

Chicago as a Railroad Center:

- Late 19th Century: Chicago’s railroads played a crucial role in the development of the city as a major industrial and commercial center. The city became known as the “Railroad Capital of the World.”

- Union Station: In 1881, Union Station was opened, consolidating the city’s passenger rail services into one major terminal. This grand station facilitated the movement of people and goods, further solidifying Chicago’s status as a railroad hub.

Innovation and Expansion:

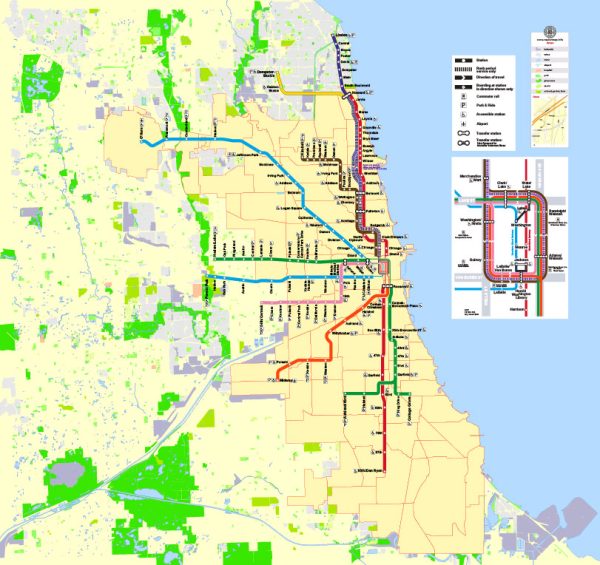

- Late 19th to Early 20th Century: Chicago witnessed innovations in rail transportation, such as the introduction of the Pullman sleeping car in the 1860s. The development of the “L” (elevated) train system in the 1890s added an additional layer to Chicago’s transportation network.

Road Systems and the Automobile Age:

- Early 20th Century: The rise of the automobile in the early 20th century prompted the development of road systems in and around Chicago. The city’s streets were gradually adapted to accommodate automobiles, leading to the establishment of a network of roads and highways.

Infrastructure Development:

- Mid-20th Century: The post-World War II era saw significant infrastructure developments, including the construction of the Eisenhower Expressway (I-290) in the 1950s. This highway played a crucial role in connecting Chicago to the suburbs and beyond.

Modern Transportation Network:

- Late 20th Century to Present: Chicago continues to be a vital transportation hub, with an extensive network of highways, railroads, and airports. The city’s transportation infrastructure is continually updated and expanded to meet the demands of a growing population and evolving economic needs.

In summary, Chicago’s history as a transportation hub is deeply intertwined with the development of its railroads and road systems. From the early days of the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad to the modern, interconnected network of highways and railroads, Chicago’s transportation infrastructure has played a pivotal role in shaping the city’s growth and economic significance.

Chicago IL: Administration and society

Government

Chicago’s government is as complex as its people, with layers of shared responsibility created by its history. The city itself is divided into 50 wards and is led by a mayor who is elected to a four-year term. However, many powers belong to the aldermen, one elected from each ward, who sit on the city council and must approve most mayoral actions. This arrangement has meant that historically the city has been governed either by forming loose coalitions and making deals or—especially during the heyday of the Democratic Party’s political “machine” (1931–78)—by controlling who got elected alderman. Mayoral control reached its zenith during the era of Richard J. Daley. The cry of one supporter that “Chicago ain’t ready for reform” began Daley’s 21-year reign, which ended with his death in December 1976. After him followed a series of short mayoralties, including those of Michael Bilandic (1976–79) and Chicago’s first female mayor, Jane Byrne (1979–83), both of whom faced unprecedented fiscal problems. During the first term of Harold Washington (1983–87), the city’s first African American mayor, conflict with a coalition of white aldermen, known locally as “Council Wars,” brought city business almost to a halt. Another African American, Eugene Sawyer, served briefly as mayor after Washington’s sudden death, but he was defeated in 1989 by Richard M. Daley, son of the former mayor. The second Daley also was able to govern with little opposition, in large part because he, like his father, developed considerable influence over the city council. Meanwhile, a series of semi-independent departments and agencies oversee such governmental responsibilities as parks, public transit, education, community colleges, water reclamation, and mosquito abatement.

Cook county, organized in 1831, reaches out well beyond the city limits, especially in the northwest. Its board is responsible for the operation of the county’s health system and extensive forest preserve district, and the county sheriff’s department patrols primarily unincorporated areas and aids in the operation of a large court system. The suburban “collar counties” of Lake, McHenry, Kane, DuPage, Will, and Kendall were once entirely rural with low population densities, but the massive influx of residents and businesses has forced them to expand services. Over time, the city and these counties together developed an identity that is distinct from “downstate,” the remainder of Illinois.

The government of the state of Illinois has a presence in Chicago not only in the form of the architecturally distinctive James R. Thompson Center downtown but also in such responsibilities as welfare, employment, and state police patrols of expressways. The overwhelmingly Democratic city and the heavily Republican downstate and suburban constituencies have long been at odds. The population parity among the three that prevailed during the mid-20th century has given way to a surging suburban presence in the legislature and a subsequent decline in power statewide by Chicago and downstate interests.

Municipal services

Gas, electric, and cable-television utilities are operated by franchised private corporations, but the water system is city-owned. Chicago not only supplies its own drinking water (drawn from inlets in the lake far from shore) but also provides it to dozens of suburbs through an extensive pipeline network. The city is also responsible for collecting trash and maintaining Chicago’s vast network of streets and alleys and its sewer system. However, wastewater treatment is the responsibility of a separate regional water-reclamation district. With well over 10,000 sworn officers on the streets, the Chicago Police Department is the biggest in the Midwest and one of the largest nationally. That status is shared by the city’s fire department, which has nearly 100 engine companies.

Drainage has been a chronic problem in Chicago. An approach taken in the late 19th century was to raise the street level several feet in the central area (many of these older structures with a below-grade first floor can still be found). The major engineering marvel of the turn of the 20th century was reversing the flow of the Chicago River so that the sewage and runoff water dumped into it no longer ran into the lake—except after heavy storms, when the locks had to be opened. The problem of untreated storm water flowing into the lake was addressed by an ambitious project popularly called Deep Tunnel. It consists primarily of a vast system of large tunnels bored in the bedrock deep beneath the region that collects and stores storm water until it can be processed at treatment facilities.

Health

During the city’s early decades, its citizens suffered through periodic epidemic scourges that killed thousands, but by the turn of the 20th century these outbreaks were largely under control, thanks mainly to improved sanitation, water filtration, and the reversed flow of the river away from the lake. Chicagoans also may feel secure in the quality of medical care available. The first line of defense is the city health department, which annually administers hundreds of thousands of immunizations at its primary care clinics and conducts tens of thousands of inspections of the city’s food establishments. The county operates an extensive system of public health-care facilities, which provide much of the treatment for the poor. The system is anchored by John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County (formerly Cook County Hospital), one of the largest such public institutions in the country with one of the busiest emergency rooms; it also operates a branch at Provident Hospital, a historic African American institution. Stroger Hospital is part of the massive Illinois Medical District on the Near West Side, a concentration of hospitals, medical schools, and other facilities. Medical schools affiliated with the University of Illinois at Chicago, Northwestern University, Loyola University, Rush University, and the University of Chicago are national leaders in several fields. In addition, dozens of hospitals are scattered throughout the metropolitan region, although hospital closings and cutbacks in federal spending have left some areas underserved.

Education

Chicago’s enormous school system has laboured to overcome long-term problems with its quality while attempting to serve diverse ethnic and social class groups. About 500 elementary and 90 secondary schools serve more than 400,000 students, many of them from impoverished families. Another 200 parochial and private schools serve some 70,000 more students.

Higher education has always lured the young to Chicago. Private church-related institutions emerged in the region during the mid-19th century, including Northwestern University, founded by Methodists in 1851, in Evanston; Lake Forest College (Presbyterian; 1857), farther up the North Shore in Lake Forest; and Wheaton College (Wesleyan Methodist; 1860), in west-suburban Wheaton. Two institutions destined to become world-renowned were founded on the city’s South Side in 1890: the University of Chicago (the second school of that name; the first, founded by Baptists in 1857, closed in 1886) and the Armour Institute of Technology (which merged with another institution in 1940 to form the Illinois Institute of Technology). Roosevelt University (1945), which occupies the historic Auditorium Building, and Columbia College (1890) are located downtown, as are branch campuses of Northwestern and of the two principal Roman Catholic institutions, DePaul (1898) and Loyola (1870) universities. Public higher education in the city took longer to emerge. The University of Illinois at Chicago (1867), which started as a two-year branch campus for World War II veterans, is the flagship among the public institutions, which include Northeastern Illinois University (1961), Chicago State University (1867), and the seven City Colleges of Chicago.

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS