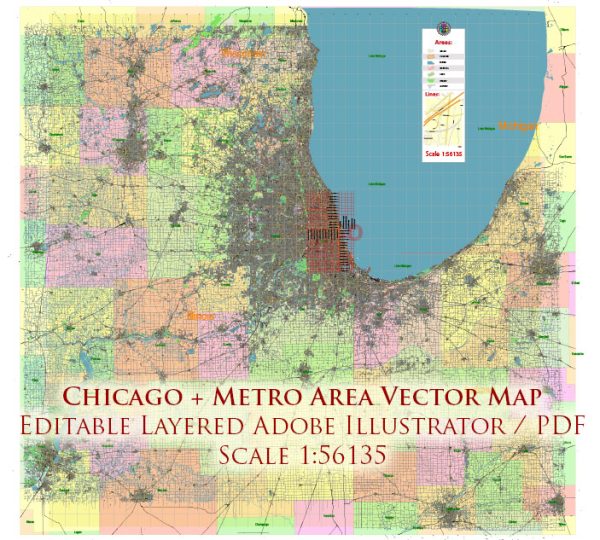

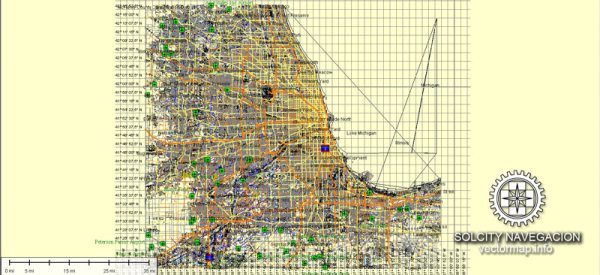

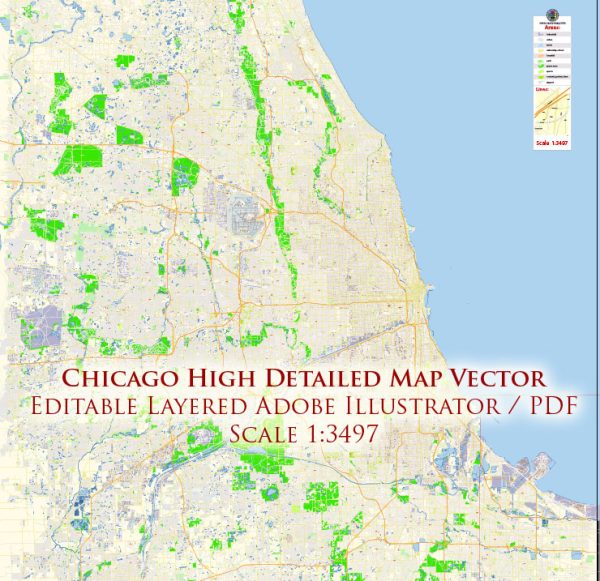

Chicago, Illinois, is a city known for its grid-like street layout, diverse neighborhoods, and iconic landmarks. The city is divided into several neighborhoods, and its street grid is generally easy to navigate. Here are some of the principal streets and roads in Chicago:

- Michigan Avenue: Also known as “The Magnificent Mile,” Michigan Avenue is a major north-south street running through the heart of downtown Chicago. It is famous for its upscale shopping, cultural institutions, and historic architecture.

- State Street: Another significant north-south street, State Street intersects with Michigan Avenue in the Loop and is known for its shopping and entertainment options.

- Lake Shore Drive: This scenic road runs along the western shore of Lake Michigan, offering stunning views of the lake and the city skyline. It’s a popular route for commuting and leisure drives.

- Wacker Drive: Wacker Drive runs along the Chicago River and is divided into Upper Wacker and Lower Wacker. It provides access to various downtown buildings and is a key route for navigating the Loop.

- Randolph Street: A major east-west street in the Loop, Randolph Street is known for its restaurants, theaters, and cultural attractions.

- Madison Street: Another important east-west thoroughfare, Madison Street runs through the Loop and connects the West Loop to the lakefront.

- Roosevelt Road: Running east-west, Roosevelt Road is a significant street connecting the Near West Side, South Loop, and near South Side neighborhoods.

- Western Avenue: As one of the longest continuous streets in Chicago, Western Avenue runs north-south, passing through various neighborhoods on the city’s North and South Sides.

- Ashland Avenue: Another major north-south street, Ashland Avenue traverses the city and is known for its commercial and residential areas.

- Archer Avenue: Connecting the southwest side of Chicago, Archer Avenue is known for its diverse communities and commercial districts.

- Halsted Street: A major north-south street, Halsted Street passes through various neighborhoods, including Greektown, Little Italy, and the Near North Side.

- Cicero Avenue: Stretching from the southwest side to the northwest side, Cicero Avenue is an important north-south thoroughfare.

These are just a few of the principal streets and roads in Chicago. The city’s grid system and the numbering of streets make navigation relatively straightforward, and many of these streets are lined with shops, restaurants, and cultural attractions. Keep in mind that Chicago is a large city with diverse neighborhoods, each offering its own unique character and charm.

Transportation in Chicago

Chicago continues to be the country’s rail transportation hub. Each day thousands of Amtrak passengers arrive or change trains at Union Station, much as railway travelers did 150 years ago. The shift of freight carriers to containers has meant that rail yards and tracks are more likely to be filled with tractor trailers and stacks of giant boxes than boxcars and gondolas. Belt railways that circle the region still provide interchange between lines, but, as rail lines have consolidated, the corporate headquarters for much of the rail industry have left the city. Despite the preeminence of the railroads in handling freight, maritime industries survived and expanded to remain competitive in high bulk–low value hauling.

From the early days of commercial aviation, Chicago’s city government has recognized and capitalized on the advantageous flexibility of air routes over more-or-less permanent railroad tracks. During the 1920s the city established Municipal Airport on the Southwest Side, which quickly developed into one of the country’s busiest air hubs. However, by the end of the 1950s, the advent of jet airliners and their requirement of longer runways threatened to make landlocked Municipal obsolete. After long debate, the city chose to build a new facility by utilizing the old Orchard Field (hence the official acronym “ORD” used on luggage tags) in northwest suburban Park Ridge. In 1949 the new airport was named in honour of Lieutenant Commander Edward (“Butch”) O’Hare, a wartime naval air hero, while Municipal was renamed Midway for the critical 1942 Allied battle victory in the Pacific. Long the undisputed busiest airport in the country, O’Hare more recently has competed with other large facilities across the country for the distinction, while a rejuvenated Midway became a regional hub. For decades the city has debated the issue of constructing a third major airport.

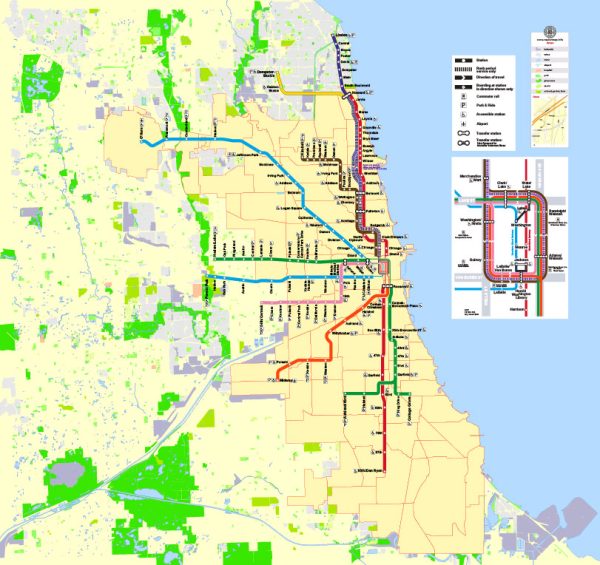

The move toward publicly operated mass transit grew out of adversity, as the Great Depression forced a collection of private streetcar and elevated-rail companies into bankruptcy. Public funding allowed the construction of a long-delayed subway system. Work began in 1938 on a north-south line under State Street that was completed in 1943, and a second, parallel route under Dearborn Street opened in 1950. These lines and the Loop elevated (“L”) structure—completed in 1897 and still the essential downtown link in the system—constitute the core of a network of rapid-transit rail lines that came to include service to O’Hare and Midway. Meanwhile, in 1945 the Illinois state legislature, the General Assembly, created the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) to take over operation of the “L” carriers; independent bus companies were absorbed in 1952.

Although Chicago grew most rapidly while it rode “L” trains and streetcars, it also fell in love with the automobile. Chicago’s expressway system dates to the 1920s, when Lake Shore Drive was rebuilt as a divided highway. (Some claim it to be one of the country’s oldest expressways.) But the postwar rush to suburbia, automobile commuting, and the 1956 Interstate Highway Act brought about the construction of the modern network. The Congress Street (later Eisenhower) Expressway to the west, completed in 1956, was the region’s first interstate highway. During the following decade, a spiderweb of Loop-directed expressways and encircling bypass routes was superimposed on the region, which roughly followed the outlines of the original wagon-wheel pattern of settlement.

The move to the automobile left public transit in crisis. In 1973 the Illinois General Assembly created the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA) and gave it the power to levy a sales tax to support the CTA as well as a failing commuter rail system (which was unified and named Metra). Privately owned and municipal bus routes in the suburbs were similarly united under the name of Pace (1983). The RTA has revitalized the system and even expanded it, notably into areas northwest and southwest of the city not previously served. In addition, there is one independent commuter rail line, the heavily subsidized South Shore Line to South Bend, Ind., the country’s sole surviving electric interurban line.

Occasionally, Chicagoans run the risk of being “bridged”—shut out of the Loop because bridges in the central area must be raised to allow passage of river traffic. There are several dozen movable bridges over waterways within the city. Two of the most noteworthy are the large double-deck Michigan Avenue and Outer Drive (or Link) bridges, the latter connecting the northern and southern parts of Lake Shore Drive. Although bridge raisings are now rare—confined largely to specified times to allow the passage of tall-masted sailboats—the river bustles in warmer weather with pleasure craft, sightseeing boats, and the occasional barge.

An aging remnant of Chicago’s infrastructure came to light dramatically in April 1992, when an under-river tunnel was punctured, leading to massive flooding in downtown basements. A system of freight tunnels had been constructed below Loop streets at the beginning of the 20th century to haul cargo, coal, and ashes to and from downtown buildings. Eventually abandoned after having served its original purpose, the system found new life carrying communications wiring and fell into obscurity until the flood. There are also unused remains of three vehicular tunnels downtown that were built under the river before 1900 because the river’s heavy shipping traffic so disrupted the use of the bridges.

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS