Economy of Chicago

Besides church steeples and skyscrapers, smokestacks have long dominated the Chicago horizon. The city’s position as a rail hub and a port aided its use of the Midwest’s raw materials to produce a wide range of goods: light manufactures such as food, food products, candy, pharmaceuticals, and soap; communication equipment, scientific instruments, and automobiles; and refined petroleum, petroleum products, and steel. The city also became a major printing and publishing centre. This diversity originally grew out of Chicago’s role as a transshipment point for eastbound grain and lumber as well as meat, which was smoked or packed in salt. The city assumed a new role as manufacturer of military supplies during the American Civil War, adding leather goods, steel rail, and food processing. Although railroading, steel, and meatpacking continued to be the largest employers, by the late 19th century manufacturing was branching into chemicals, furniture, paint, metalworking, machine tools, railroad equipment, bicycles, printing, mail-order sales, and other fields that were considered the cutting edge in their day. The production of most of the country’s telephone equipment made Chicago the Silicon Valley of an earlier era. Industrial diversification also depended on a skilled workforce, whose numbers were enhanced through a tradition of innovative vocational training.

Manufacturing

Although Chicago failed to attract the automobile-manufacturing dominance it sought, its other industries thrived through much of the 20th century. It became a major radio and electronics centre during the 1920s. Like all manufacturing cities, Chicago was devastated by the Great Depression. The World War II boom involved more than 1,400 companies producing a wide range of military goods. Diversification, however, also made Chicago’s job market vulnerable to changes in almost any industry. In addition, the city’s abundant multistory factory buildings, which were often located in congested districts, could not compete with newer suburban industrial parks that had their sprawling single-story plants and access to expressways. Many companies sought new (and cheaper) labour markets south and west in the Sun Belt or overseas while keeping their headquarters in Chicago. Estimates of industrial jobs lost during the first four postwar decades run as high as one million, but manufacturing has remained a significant—if diminished—component of the regional economy.

Finance and other services

The drop in manufacturing’s preeminence has been mirrored by a dramatic rise in the service sector, which now employs some one-third of the city’s workforce. Notably, Chicago has fallen back on its original preindustrial role as a trading centre. The city’s rapid early growth and its location as the rail hub amid the country’s farm belt made it the logical site for commodities trading. In 1848, traders created the Chicago Board of Trade to rationalize the process of purchasing and forwarding grain to Eastern markets. Over the years the scope of its trading expanded to include a number of commodities, and in 1973 it spun off an independent Chicago Board Options Exchange to regularize trading of corporate stock options. Meanwhile, in 1874 the new Chicago Produce Exchange began providing trading services for butter, eggs, poultry, and other farm product markets; in 1919 it changed its name to the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. The fourth trading institution, the Chicago Stock Exchange, was organized in 1882 to handle corporate securities; mergers with exchanges in other cities led to it being renamed the Midwest Stock Exchange in 1949, but the original name was restored in 1993. All four of these institutions—along with trading, banking, and other financial functions—have made the downtown LaSalle Street district synonymous with Chicago’s regional dominance, though the long-standing tradition of face-to-face trading that built them has experienced increased competition from electronic trading.

Chicago, with dozens of major banks, remains second only to New York City as a national financial hub. However, local wholesaling and retailing have fallen increasingly under the control of out-of-town interests, which have either bought out or squeezed out department stores and retailers in several product lines.

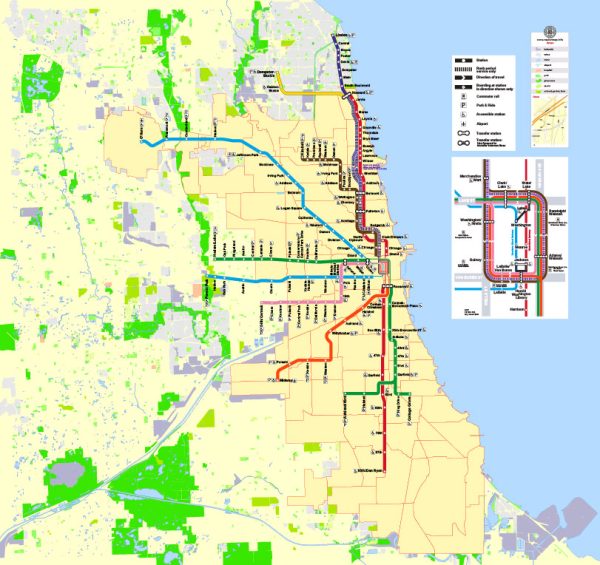

Chicago’s position as a national transportation hub has long guaranteed the city a steady stream of conventions and trade shows. It has hosted numerous national political conventions since the one in 1860 that nominated Abraham Lincoln for the presidency. Older venues such as the Coliseum, the International Amphitheater, and the Chicago Stadium have given way to the United Center and the UIC Pavilion in the city and the Allstate Arena in suburban Rosemont, near O’Hare. McCormick Place, the lakefront convention complex just south of downtown, has been expanded several times to remain among the largest trade-show facilities in the country. Each year, McCormick Place alone hosts dozens of conventions and trade shows that draw many hundreds of thousands of people and pump considerable revenue into the local economy. Millions more businesspeople, tourists, and other short-term visitors come to the city annually to shop, dine, visit museums, and take in sporting and musical events, many of them staying in the region’s tens of thousands of hotel rooms.

Source: https://www.britannica.com/place/Chicago/People

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS