History of Alaska

Early history

People have inhabited Alaska since 10,000 BCE. At that time a land bridge extended from Siberia to eastern Alaska, and migrants followed herds of animals across it. Of these migrant groups, the Athabaskans, Unangan (Aleuts), Inuit, Yupiit (Yupik), Tlingit, and Haida remain in Alaska.

Explorations

As early as 1700, Indigenous peoples of Siberia reported the existence of a huge piece of land lying due east. In 1728 an expedition commissioned by Tsar Peter I (the Great) of Russia and led by a Danish mariner, Vitus Bering, determined that the new land was not linked to the Russian mainland, but, because of fog, the expedition failed to locate North America. On Bering’s second voyage, in 1741, the peak of Mount St. Elias was sighted, and men were sent ashore. Sea otter furs taken back to Russia opened a rich fur commerce between Europe, Asia, and the North American Pacific coast during the ensuing century.

Russian settlement

The first European settlement was established in 1784 by Russians at Three Saints Bay, near present-day Kodiak. With the arrival of the Russian fur traders, many Unangan were killed by the newcomers or overworked in the hunting of fur seals. Many other Unangan died of diseases brought by the Russians.

Kodiak served as Alaska’s capital until 1806, when the Russian-American Company, organized in 1799 under charter from the emperor Paul I, moved its headquarters to Sitka, where there was an abundance of sea otters. The chief manager of the company’s operations (essentially the governor of the Russian colonies), Aleksandr Baranov, was an aggressive administrator. His first effort to establish a settlement at Old Harbor near Sitka was destroyed by the Tlingit. His second attempt, in 1804 at Novo-Arkhangelsk (“New Archangel”; now Sitka), was successful, but not without a struggle that resulted in the battle of Sitka, the only major armed conflict between Alaska Natives and Europeans. (Nevertheless, Alaska Natives continued to agitate for land rights; some of their demands finally were met with the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971.) Yet, compared with the previous Russian fur traders, the Russian-American Company maintained relatively good relations with the Unangan and the Indigenous peoples of the southeast, as well as with the Yupiit of the lower Yukon and Kuskokwim river valleys. It was not uncommon for Unangan to marry Russians and convert to the Russian Orthodox faith, and quite a few Unangan—some with Russian surnames—worked for the Russian-American Company.

During this time, British and American merchants were rivals of the company. A period of bitter competition among fur traders was resolved in 1824 when Russia concluded separate treaties with the United States and Great Britain that established trade boundaries and commercial regulations. The Russian-American Company continued to govern Alaska until the region’s purchase by the United States in 1867.

U.S. possession

The near extinction of the sea otter and the political consequences of the Crimean War (1853–56) were factors in Russia’s willingness to sell Alaska to the United States. U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward spearheaded the purchase of the territory and negotiated a treaty with the Russian minister to the United States. After much public opposition, Seward’s formal proposal of $7.2 million was approved by the U.S. Congress, and the American flag was flown at Sitka on October 18, 1867. The Alaska Purchase was initially referred to as “Seward’s Folly” by critics who were convinced the land had nothing to offer.

As a U.S. possession, Alaska was governed by military commanders for the War Department until 1877. During these years there was little internal development, but a salmon cannery built in 1878 was the beginning of what became the largest salmon industry in the world. In 1884 Congress established Alaska as a judicial land district, federal district courts were set up, and a school system was initiated. In 1906 Alaska’s first representative to Congress, a nonvoting delegate, was elected, and in 1912 Congress established the Territory of Alaska, with an elected legislature.

Meanwhile, gold had been discovered on the Stikine River in 1861, at Juneau in 1880, and on Fortymile Creek in 1886. The stampede to the Atlin and Klondike placer goldfields of adjoining British Columbia and Yukon territory in 1897–1900 led to the development of the new Alaska towns of Skagway and Dyea (now a ghost town), jumping-off points to the Canadian sites. Gold discoveries followed at Nome in 1898, which brought prospectors back from Canada, and at Fairbanks in 1903. The gold rush made Americans aware of the economic potential of this previously neglected land. The great hard-rock gold mines in the panhandle were developed, and in 1898 copper was discovered at McCarthy. Gold dredging in the Tanana River valley began in 1903 and continued until 1967.

A dispute between the United States and Canada over the boundary between British Columbia and the Alaska panhandle was decided by an Alaska Boundary Tribunal in 1903. The U.S. view that the border should lie along the crest of the Boundary Ranges was accepted, and boundary mapping was mostly completed by 1913. Between 1898 and 1900 a narrow-gauge railroad was built across White Pass to link Skagway to Whitehorse, in the Yukon, and shortly afterward the Cordova-to-McCarthy line was laid up the Copper River. Another railway milestone, and the only one of these lines still operating, was the approximately 500-mile (800-km) Alaska Railroad that connected Seward with Anchorage and Fairbanks in 1923. In 1935 the government encouraged a farming program in the Matanuska valley near Anchorage, and dairy cattle herds and crop farming were established there, as well as in the Tanana and Homer regions.

In 1942, during World War II, Japanese forces invaded Agattu, Attu, and Kiska islands in the Aleutian chain and bombed Dutch Harbor on Unalaska. This aggression prompted the construction of large airfields, as well as the Alaska Highway, more than 1,500 miles (2,400 km) of road linking Dawson Creek, British Columbia, with Fairbanks. Both proved later to be of immense value in the commercial development of the state.

During the war, the U.S. army uprooted most of the Unangan from the Aleutian Islands and sent them to work in canneries, sawmills, hospitals, and schools or to internment camps in Juneau or on the southeastern islands. Disease—particularly influenza and tuberculosis—killed many Unangan during this period. After the war, numerous Unangan returned to the Aleutians, but others stayed in southeastern Alaska.

Alaska since statehood

Alaskans voted in favour of statehood in 1946 and adopted a constitution in 1956. Congressional approval of the Alaska statehood bill in 1958 was followed by formal entry into the union in 1959.

During the 20th century nearly 40 earthquakes measuring at least 7.25 on the Richter scale were recorded in Alaska. The devastating Alaska earthquake on March 27, 1964, affected the northwestern panhandle and the Cook Inlet areas, destroying parts of Anchorage; a tsunami that followed wiped out Valdez; the coast sank 32 feet (9.75 metres) at Kodiak and Seward; and a 16-foot (4.9-metre) coastal rise destroyed the harbour at Cordova.

Oil and natural gas discoveries in the Kenai Peninsula and offshore drilling in Cook Inlet in the 1950s created an industry that by the 1970s ranked first in the state’s mineral production. In the early 1960s a pulp industry began to utilize the forest resources of the panhandle. Major paper pulp mills were constructed at Ketchikan and Sitka, largely to serve the Japanese market. These mills closed in the 1990s because of logging restrictions.

In 1968 the discovery of petroleum on lands fronting the Arctic Ocean gave promise of relief for Alaska’s economy, but the problem of transportation across the state and to the rest of the country held up exploitation of the finds. In 1969 a group of petroleum companies paid the state nearly $1 billion in oil land revenues, but the proposed pipeline across the eastern Brooks Range, interior plains, and southern ranges to Valdez created heated controversies between industry, government, and conservationists. In November 1973 a bill passed the U.S. Congress that made possible construction of the 800-mile (1,300-km) Trans-Alaska Pipeline, which began the following year and was completed on June 20, 1977. As a result, oil flows freely from the Prudhoe Bay oil field on the Arctic coast to the ice-free harbour at Valdez, whence tankers transport it to U.S. West Coast ports.

In 1989 the oil tanker Exxon Valdez ran off course in Prince William Sound, causing the most disastrous oil spill in North American history and inflicting enormous damage on the area’s marine ecology and local economy. A massive cleanup effort was undertaken, but only about one-seventh of the oil was recovered. The issue was resolved when the Exxon oil company agreed to pay a $900 million settlement to the federal and Alaskan governments. Another disastrous oil spill occurred in 2004, when a vessel broke apart in the Aleutian Islands and released about 350,000 gallons (1,320,000 litres) of fuel oil into the ocean. Yet another spill, the largest in the history of the pipeline, occurred in 2006 when a transit pipe at BP’s Prudhoe Bay facility ruptured, spreading more than a quarter million gallons (one million litres) of oil onto the tundra. Those catastrophes, however, opened wider the doors to the debate on preservation versus oil exploitation.

In the early 21st century, declining oil production was a major concern of Alaskans. The issue of whether to drill in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, in the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska, and in the Beaufort and Chukchi seas continued to be hotly debated, and U.S. government policy regarding it flip-flopped between Democratic and Republican administrations. In December 2016 Democratic Pres. Barack Obama issued a pair of memorandums that indefinitely banned oil and gas development in the entirety of the U.S. portion of the Chukchi Sea and the majority of the Beaufort Sea. Roughly a year later the Republican-controlled Congress passed legislation that lifted the longtime ban on oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and in January 2021 Obama’s successor, Republican Donald Trump, oversaw the sale of oil-drilling leases in the refuge. Democrat Joe Biden, who replaced Trump in the White House, suspended those drilling leases in June 2021.

A general overview of the economic and industrial aspects of Alaska.

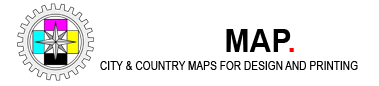

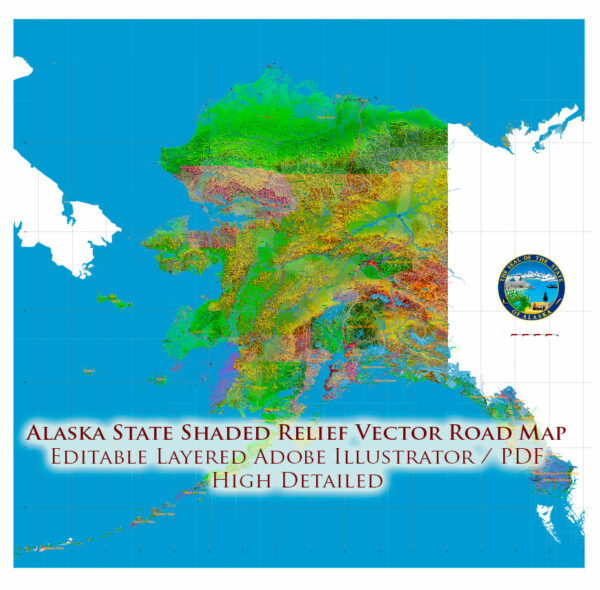

Vectormap.Net provide you with the most accurate and up-to-date vector maps in Adobe Illustrator, PDF and other formats, designed for editing and printing. Please read the vector map descriptions carefully.

Economic Overview: Alaska has a unique economic structure compared to other U.S. states due to its vast size, remote location, and rich natural resources. The state’s economy is heavily dependent on the oil and gas industry, with revenues from oil production playing a crucial role in funding the state budget.

- Oil and Gas Industry:

- Alaska’s North Slope is home to some of the largest oil fields in North America, including Prudhoe Bay. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline transports crude oil from the North Slope to the ice-free port of Valdez.

- The state government relies heavily on oil revenues to fund public services, and fluctuations in oil prices can have a significant impact on the state’s budget.

- Tourism:

- Alaska’s natural beauty and diverse ecosystems attract tourists from around the world. The state is known for its stunning landscapes, wildlife, and outdoor recreational opportunities.

- Tourism contributes significantly to Alaska’s economy, providing jobs and income for businesses in the hospitality, transportation, and recreational sectors.

- Fishing and Seafood Industry:

- Alaska is a major player in the U.S. fishing industry, particularly in the harvesting of wild salmon, crab, and other seafood.

- The state’s fisheries contribute to both domestic and international markets, and the seafood industry is a vital source of employment for many Alaskans.

- Mining:

- Alaska has rich mineral resources, including gold, zinc, copper, and other minerals. The mining industry plays a role in the state’s economy, although it is not as dominant as oil and gas.

- The development of mining projects can have environmental considerations, and there are regulations in place to balance economic interests with environmental protection.

- Military Presence:

- The military is a significant contributor to Alaska’s economy, with several military bases located in the state. These bases provide jobs and support local businesses.

- Transportation and Logistics:

- Due to its vast size and challenging terrain, transportation and logistics are critical in Alaska. The state relies on air, sea, and land transportation for the movement of goods and people.

- Renewable Energy:

- Given its abundant natural resources, Alaska has been exploring and investing in renewable energy sources, such as wind, hydroelectric, and geothermal power, to reduce dependency on fossil fuels.

Challenges:

- Alaska faces economic challenges due to its reliance on oil revenues, which can be volatile.

- The state also grapples with issues related to climate change, affecting its ecosystems, infrastructure, and traditional ways of life.

It’s essential to check more recent sources for the latest information on Alaska’s economic and industrial landscape, as conditions may have evolved since my last update.

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS