Map Generalization

How to Control Detail Without Destroying Shape

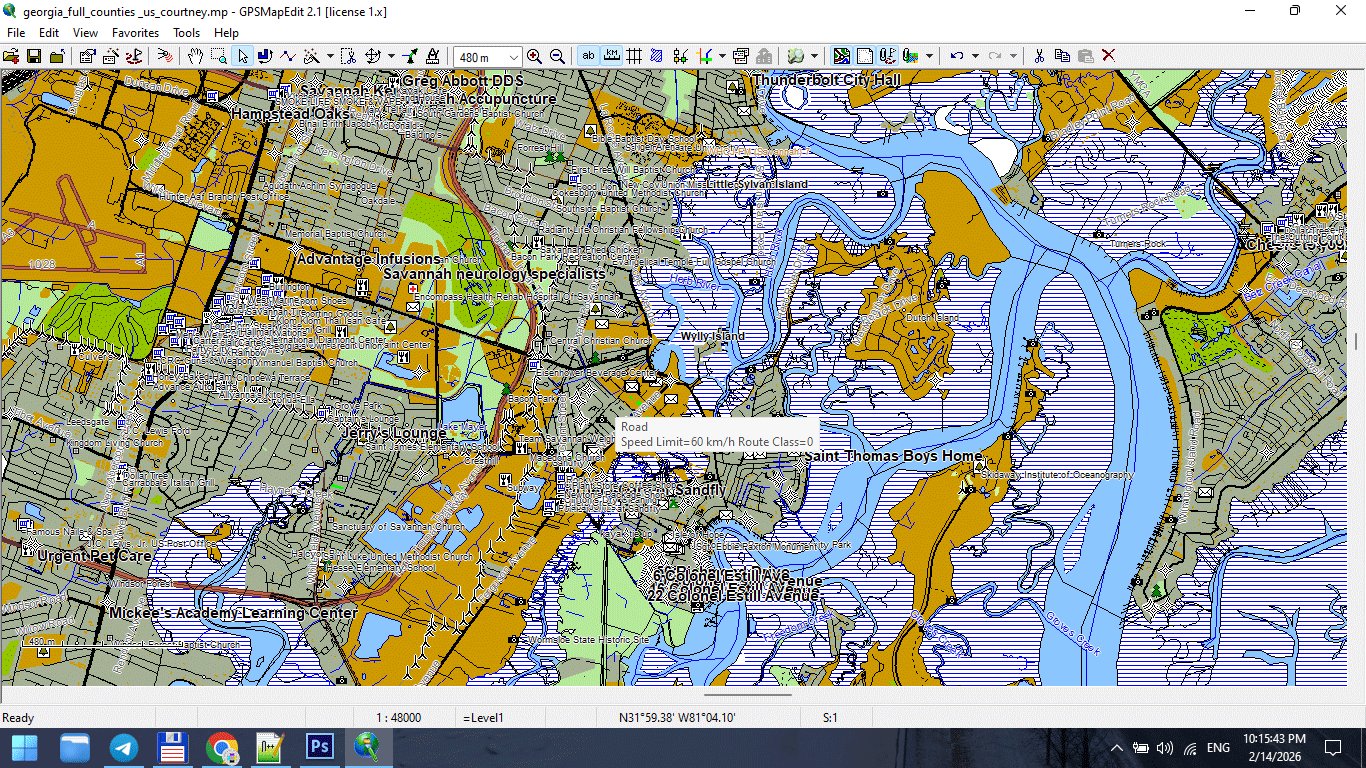

When beginners first see raw geodata,

they are impressed.

So many details.

So many vertices.

So much precision.

Then they try to print it.

And everything collapses.

Coastlines look noisy.

Roads look tangled.

File size explodes.

Illustrator slows down.

This is where generalization begins.

Figure 1. High-Detail Map at Large Scale.

What Is Map Generalization?

Map generalization is the controlled simplification of geographic data to match map scale and purpose.

It is not random deletion.

It is structured reduction.

Generalization allows you to:

-

Reduce visual noise

-

Improve readability

-

Stabilize file performance

-

Maintain recognizable shapes

-

Adapt data to print scale

Generalization is not data loss.

It is editorial decision-making.

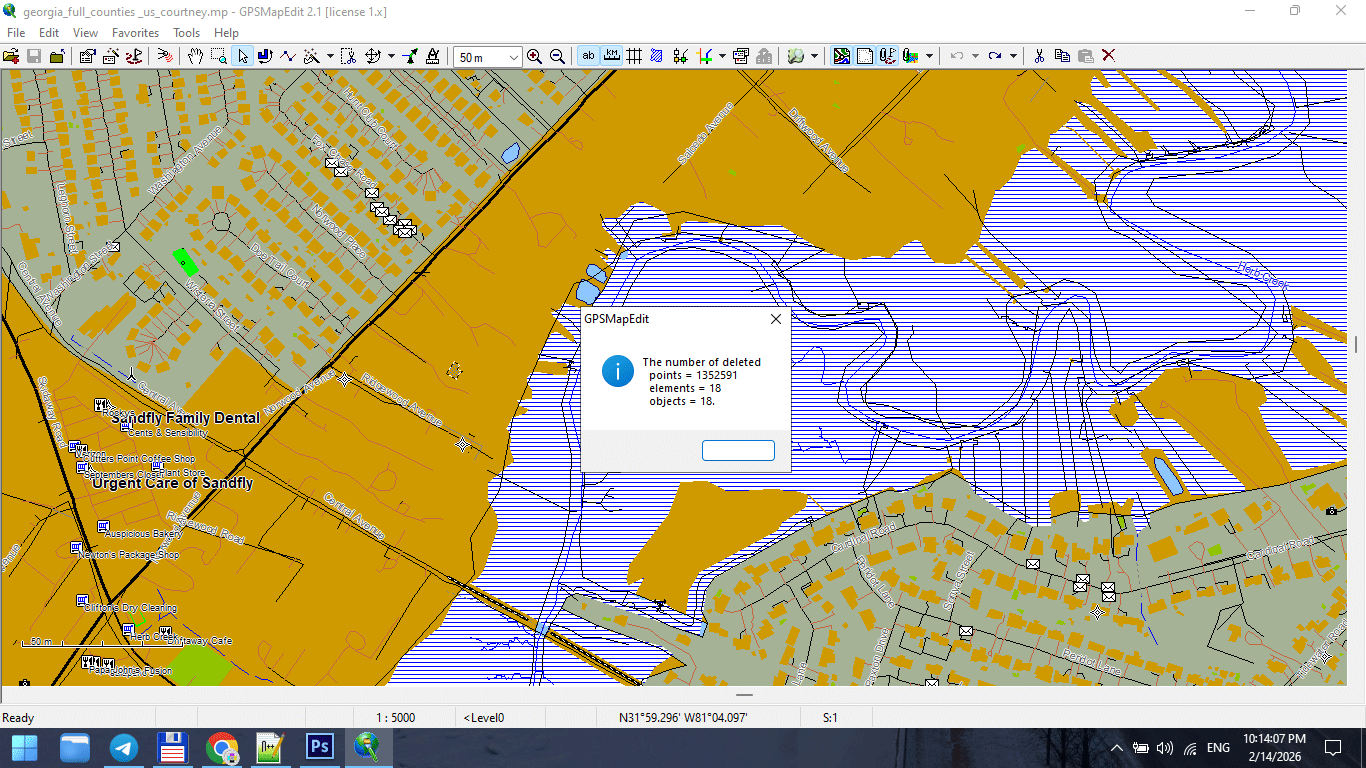

Figure 2. Line Simplification During Generalization.

Why Raw Data Is Not Print-Ready

Raw GIS datasets are built for:

-

Analysis

-

Measurement

-

Data storage

They are not built for:

-

Large-format wall maps

-

Visual clarity

-

Typography balance

-

Stroke hierarchy

Raw data is often:

-

Over-detailed

-

Fragmented

-

Over-segmented

-

Topologically heavy

If you skip generalization,

your print map will suffer.

The Relationship Between Scale and Detail

This is the key principle:

Generalization must match the final print scale — not the original data precision.

Example:

If your dataset contains 1-meter precision,

but your map scale is 1:250,000,

most of that detail is invisible and unnecessary.

Too much detail at small scale creates noise.

Less detail at large scale improves clarity.

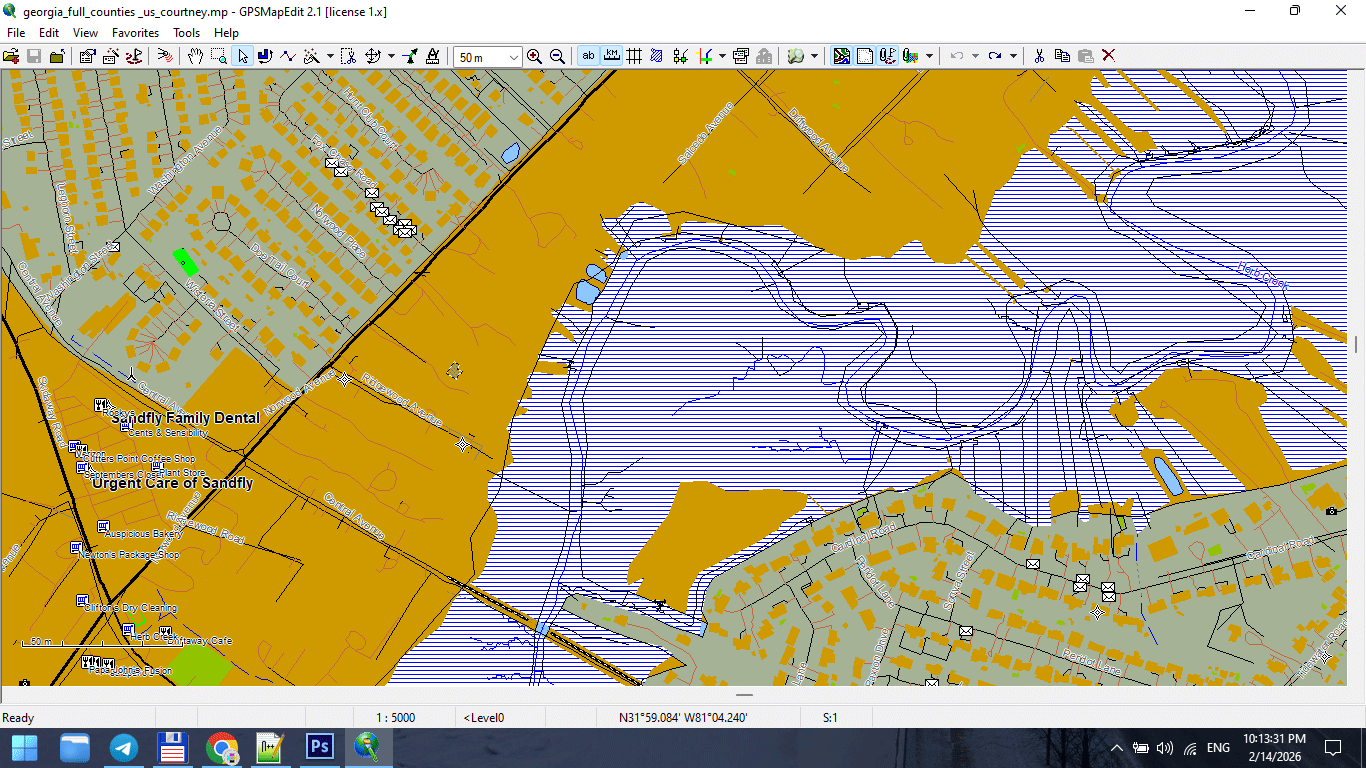

Figure 3. Small-Scale Map After Feature Generalization.

Types of Generalization

Professional cartography uses multiple forms of generalization.

1. Geometric Simplification

Reduces the number of vertices in lines and polygons.

Common algorithm:

Douglas–Peucker simplification.

Goal:

Preserve overall shape while reducing node count.

Danger:

Too aggressive simplification destroys coastline identity.

2. Topological Generalization

Maintains logical relationships between objects.

Ensures:

-

Roads remain connected

-

Polygons remain closed

-

Boundaries remain consistent

Never simplify geometry without preserving topology.

3. Semantic Generalization

Removes entire object classes based on scale.

For example:

At 1:5,000,000 scale:

-

Residential streets disappear

-

Small rivers disappear

-

Minor buildings disappear

This is not simplification —

it is selective omission.

4. Smoothing

Reduces sharp angles and visual “noise.”

Useful for:

-

Coastlines

-

Natural boundaries

-

Rivers

Must be applied carefully.

Over-smoothing destroys geographic character.

When to Generalize

Generalization should occur:

-

After topology cleaning

-

Before final Illustrator export

-

After classification standardization

Do not generalize raw, uncleaned data.

Fix structure first.

Simplify second.

Common Beginner Mistakes

-

Applying maximum simplification

-

Using the same tolerance for all layers

-

Simplifying roads and coastlines equally

-

Ignoring scale

-

Forgetting to save intermediate versions

Generalization is not “click once and done.”

It requires testing.

Practical Generalization Strategy

Instead of asking:

“How much can I simplify?”

Ask:

“How much can I remove while preserving recognizability?”

Guidelines:

-

Coastlines → light simplification

-

Administrative boundaries → moderate

-

Roads → controlled and tested

-

Buildings → often semantic removal at smaller scales

Tolerance and Scale

Tolerance values depend on:

-

Map scale

-

Geographic extent

-

Printing size

Example logic:

-

Large-scale city map → minimal simplification

-

Regional map → moderate simplification

-

National map → strong simplification

-

World map → aggressive semantic filtering

There is no universal number.

Only context.

Performance and Stability Benefits

Proper generalization:

-

Reduces file size

-

Speeds up Illustrator

-

Prevents export crashes

-

Improves stroke clarity

-

Enhances label placement

Unnecessary vertices are invisible in print

but destructive in production.

Recognizability Rule

After simplification:

-

Does the coastline still look correct?

-

Does the river still follow its natural curve?

-

Does the city still feel authentic?

If not — you simplified too much.

Recognizability is more important than geometric purity.

Professional Workflow Tip

Always keep versions:

map_generalized_v1.shp

map_generalized_v2.shp

Never overwrite your clean dataset.

You may need to adjust tolerance later.

Generalization in Software

Most GIS tools include:

-

Simplify Lines

-

Simplify Polygons

-

Topology-preserving simplification

But remember:

The tool does not decide quality.

You do.

Generalization is editorial judgment.

Summary

Map generalization is:

-

Controlled simplification

-

Scale adaptation

-

Performance optimization

-

Visual clarity management

It is not data destruction.

It is professional refinement.

Without generalization,

print cartography becomes unstable.

With correct generalization,

complex geography becomes readable.

Next Chapter

Now that the geometry is optimized,

we move to file formats and export logic.

→ Chapter 7 — Vector Formats: SHP, GeoJSON, AI and PDF

Go to Start Page: Technology of Vector Map Production

Frequently Asked Questions

What is map generalization?

Map generalization is the controlled simplification of geographic data to match scale and improve readability.

What happens if I over-generalize?

Geographic shapes lose recognizability and become unrealistic.

Is generalization necessary for large maps?

Yes. Without simplification, files become heavy and visually noisy.

Should all layers use the same simplification tolerance?

No. Different object types require different levels of simplification.

Table of contents

Chapter 1 — What Is a Vector Map?

Chapter 2 — Obtaining and Preparing Geodata (SHP, OSM, GeoJSON)

Chapter 3 — Street Network as a Graph (Nodes and Edges Explained)

Chapter 4 — Cartographic Layer Hierarchy and Visual Structure

Chapter 5 — Map Projections and Why Distortion Is Inevitable

Chapter 6 — Map Generalization and Scale Control

Chapter 7 — Vector Formats: SHP, GeoJSON, AI and PDF

Chapter 8 — Professional Map Production Workflow

Chapter 9 — Preparing a Vector Map for Print in Illustrator

Chapter 10 — Common Mistakes in Vector Map Production

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS

Author: Kirill Shrayber, Ph.D. FRGS