History of Jewish Cartography: we open this world for you

Radhanites, Ladino, Jewish Mediterranean merchants and corsairs

History of Jewish Cartography: we open this world for you

The Radhanites: “highways” between worlds (8th–10th c.)

Jewish Radhanites were a trans‑Eurasian network of broker‑merchants: they kept contact between the Latin West and the Islamic East when direct ties were often politically impossible. Ibn Khordadbeh’s Book of Roads and Kingdoms (c. 870) describes them in detail: multilingual agents (Persian, Arabic, “Roman”/Greek, “Andalusian,” “Saqaliba”/Slavic, etc.), four main thoroughfares from the Rhône and Provence to India and China, cargoes of small volume and high value (silk, spices, aromatics, furs, arms, etc.). Exactly this logistics of knowledge (how to go, where to pay dues, whom to approach) became the “raw material” for early route schemes and descriptions.

Debate on origins. Historiography (Moshe Gil) often links the name to the region of Radhan in southern Iraq and to a segment of the network based there; the question of “eastern” or “western” origin remains debated.

Ladino: the language of diasporic trade (late medieval / early modern)

Ladino (Judeo‑Spanish) arose among Iberian Sephardim and after 1492 became a portable “commercial” code in the Ottoman and Eastern Mediterranean world: an Old Spanish base plus layers of Hebrew/Aramaic, later Turkish, Greek, Italian. For a merchant it was a universal key to the ports of Salonika, Istanbul, Smyrna, Alexandria and Livorno, over which letters in local koine (Arabic, Turkish, etc.) could be easily laid.

“Sea and cutlass”: merchants, privateers, corsairs

In the 16th–17th centuries the Sephardi network operated at the junction of trade, diplomacy and licensed privateering. A few illustrative figures:

Samuel Pallache (c. 1550–1616) — Moroccan‑Jewish merchant and diplomat at the Saadi court, a negotiator with the Dutch Republic. Held letters of marque against Spanish ships; at the same time built trade lines Morocco ↔ Netherlands and took part in the birth of Amsterdam’s Sephardi community. His biography is examined in detail by M. García‑Arenal and G. Wiegers (A Man of Three Worlds).

Moses (Moisés) Cohen Henriques (17th c.) — a Sephardi privateer in the service of the Dutch West India Company; in 1628 helped Admiral Piet Hein capture the Spanish Silver Fleet in Matanzas Bay (Cuba) — a classic episode of “economic warfare” over sea communications.

Sinan Reis (Sinan “the Jew”?) — an Ottoman corsair and commander from Barbarossa’s circle. Modern works often ascribe to him Sephardi origins; however, Ottoman primary sources are silent, and his ethnicity remains disputed.

History of Jewish Cartography: we open this world for you

How it worked in practice

Hybrid roles. The same person could be a merchant, translator, market scout and aggregator of political information; a privateering license turned a merchantman into an instrument of pressure against a hostile crown.

Letters and chanceries. Commercial letters and chits (often in Judeo‑Arabic, later in Ladino/Italian) were a key bearer of “geography”: prices in ports, depths, pilotage cues, quarantines. A huge body of evidence is the Cairo Geniza (11th–13th c.), studied by S. D. Goitein.

From the Radhanite arteries to the Sephardi Mediterranean network — it is one logic: multilingualism, trusted channels, letters as a “map in text,” and at the frontiers — licensed force (corsairing) as a continuation of trade by other means.

Jews in the Arab–Islamic scholarly world (9th–12th c.): sofers, correspondence, maps

Who is a sofer and why it matters for geography

A sofer is a professional scribe, first of all of sacred texts (STaM: Sefer Torah, tefillin, mezuzot). In the real life of the diaspora a sofer often combined sacred work with clerical and commercial functions: kept letters, copied contracts, compiled inventories of goods, translated, made extracts from travel notes and tables. This is precisely the “bureaucratic infrastructure of writing” on which trade, route knowledge and information exchange between communities rested.

Technical requirements for the sofer (professional standard)

Materials and tools: kosher parchment, indelible black ink, goose/reed quill.

Body size, letterforms, ruling: strict proportions for each letter, ruling (sirtut), crowns (tagin) on required letters, equal line height.

Writing procedure: intention lishmah (for the sake of the commandment), pronouncing words before writing, a ban on “gluing” letters, immediate checking. Any error in a sacred text invalidates the leaf, sometimes the entire scroll.

Knowledge of norms: Masorah (the precise text tradition), grammar, unpointed orthography, the ability to audit oneself and others.

History of Jewish Cartography: we open this world for you

Discipline and exactness: a “clockmaker’s craft” — slowly, without distractions, with regard to humidity/temperature so the ink does not “bleed.”

This school of extreme precision made the sofer an ideal copyist of any complex information: calendrical tables, accounts, star‑based navigation coordinates and coastal landmarks, routes and port tariffs. Therefore, in the diaspora sofers often moonlighted as secretaries, notaries, translators — those who turn oral geography and market rumor into reliable text.

Hence surnames/nicknames like Escrivá / Escriba / Escribano (“scribe,” “notary” in Romance lands). In the Iberian‑Sephardi milieu such professional cognomens were borne both by people actually engaged in writing and notarial work and by their descendants.

Jews and the Arab–Islamic “science of writing” (katibs, chanceries, languages)

The world of the 9th–12th centuries is the chanceries (diwans) of Baghdad, Qayrawan, Fustat, Cordoba; it is katibs (secretaries), translators, notaries. Jews held recognized niches in these ecosystems:

Language competence: Hebrew/Aramaic + Judeo‑Arabic (Arabic written in Hebrew script) — an ideal bundle for correspondence between East and West; later in the western Mediterranean a Romance line was added (Latino‑Romance, proto‑Ladino koine).

History of Jewish Cartography: we open this world for you

Functions: drafting business letters, contracts, customs inventories, translating maritime statutes, checking measures and weights, keeping archives.

Result: a stable postal‑commercial network of communities in which the letters of rabbis, merchants and scholars travelled through the same channels.

“The diaspora’s post”: rabbinic correspondence and business letters

From the exile from Judea onward, century after century, Jewish communities never for long lost their international correspondence:

Responsa (she’elot u‑teshuvot) — legal‑religious replies by rabbis to queries from other lands. These are the “nerves” of the network: from Babylonia to the Maghreb, from the Maghreb to al‑Andalus, from Egypt to Italy and back.

Business letters — the same channels, but contents: prices in ports, seasons of winds and caravans, dues, reliable captains, dangerous straits, quarantines, “blacklists.”

Geography in the text: letters play the role of itineraries — step‑by‑step descriptions of roads and seas. For a cartographer this is raw material: names of harbors, day‑run distances, “turning points” (cape, island, reef).

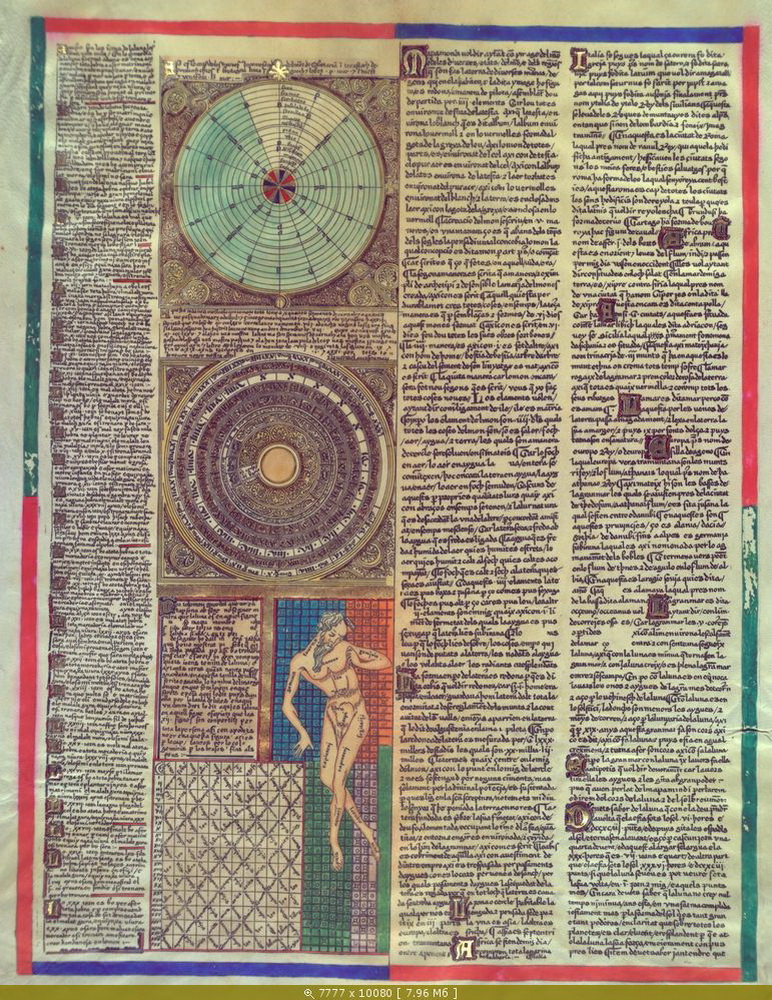

Scientific bundle: calendar, astronomy, instruments

The Arab‑Islamic world supplied the language and methods, and Jewish scholars embedded them in their own corpus — from the calendar to the astrolabe.

Calendar (ibbur): computing new moons, intercalations, comparing lunar‑solar cycles. This is not “pure theology” but exact astronomy; the same tables and techniques serve for latitude estimates and timekeeping — therefore indirectly work for navigation.

Astrolabe: a universal instrument for measuring the altitude of celestial bodies. Jewish authors and copyists copied and adapted treatises on the astrolabe’s construction and use, compiling in Hebrew and Judeo‑Arabic instructions “how to measure” and “how to compute.”

Qibla and directions: in Islamic tradition — determining the azimuth of Mecca; in Jewish practice — orientation toward Jerusalem. This is the same spherical geometry of directions, the same trigonometry — and the same discipline of precision that the sofer teaches.

History of Jewish Cartography: we open this world for you

People and roles (9th–12th c.) — briefly, to the point

The “universal sofer” (a type, not one person): scrolls, marriage contracts (ketubbot), debt notes, translation from Arabic “into Hebrew letters,” extracts from calendrical and astronomical tables. Such a master easily “lays into text” route experience — accurately, without loss.

Saadia Gaon (10th c.): head of the academy in Sura, systematizer of the calendar, author in Judeo‑Arabic; his computational culture is a bridge between ritual time and practical astronomy.

Mashallah ibn Athari (8th–9th c.) and followers: a corpus of treatises on the astrolabe and the sphere that was actively copied and entered Jewish and Latin milieus; they are measuring manuals for all who draw celestial‑terrestrial schemes.

Abraham bar Hiyya (12th c.): Hebrew language for exact mathematics (geometry, trigonometry), suitable for surveying and cartographic tasks; forms a “lexicon of formulae” in Hebrew.

Abraham ibn Ezra (12th c.): popularizer of astronomy and calendrics; transfers Arabic methods onto Jewish ground, giving “instrumental” literacy to a broad circle.

History of Jewish Cartography: we open this world for you

How this ties to cartography

Writing → schema. When a trade agent describes a fairway or caravan track, the sofer turns it into a normative text — suitable for repeated copying. The next copyist will add marginalia: “from cape to cape — a day’s run,” “caution: shoal.”

Tables → coordinates. Calendrical and astronomical tables teach the habit of calculating and checking — without it neither portolans nor later “stellar” latitude methods are possible.

Archive → memory of routes. The preservation of documents (geniza, communal chests, home archives) turns the network into a store of geography. Where maps are not drawn, they are replaced by letters; where maps appear, a textual base already exists.

Summary of the section

A sofer is not only a “man of the Torah,” but also an engineer of text: extreme precision, strict procedure, skill with tables and norms.

The postal‑commercial network of rabbis and merchants is a “continental internet” of the 9th–12th centuries that never goes dark for long: from Baghdad to the Maghreb, from Fustat to Cordoba, from Qayrawan to Provence.

Arabic scientific language + Jewish correspondence = a milieu where geography, the calendar and navigational practice merge. Out of this milieu the later portolan and “atlas” tradition will grow.

History of Jewish Cartography: we open this world for you

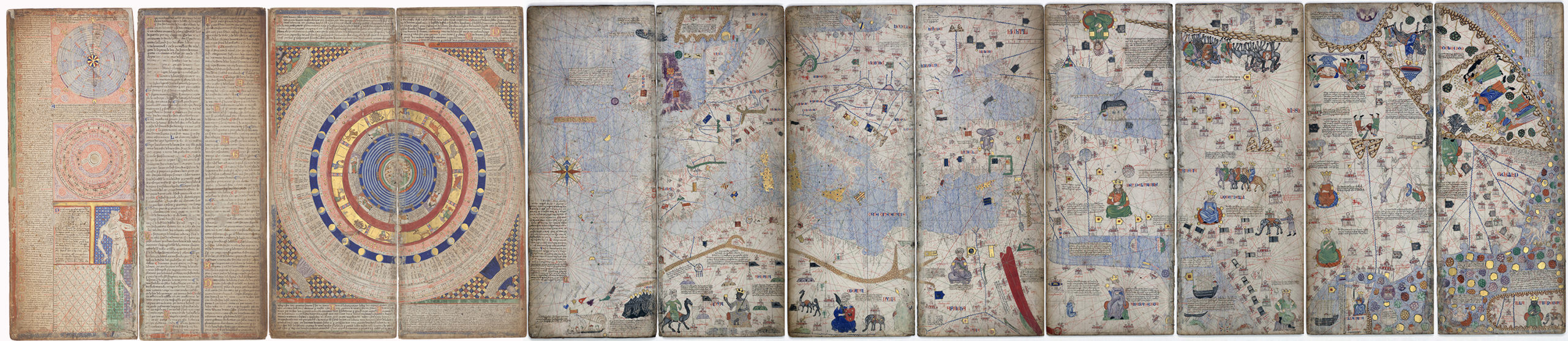

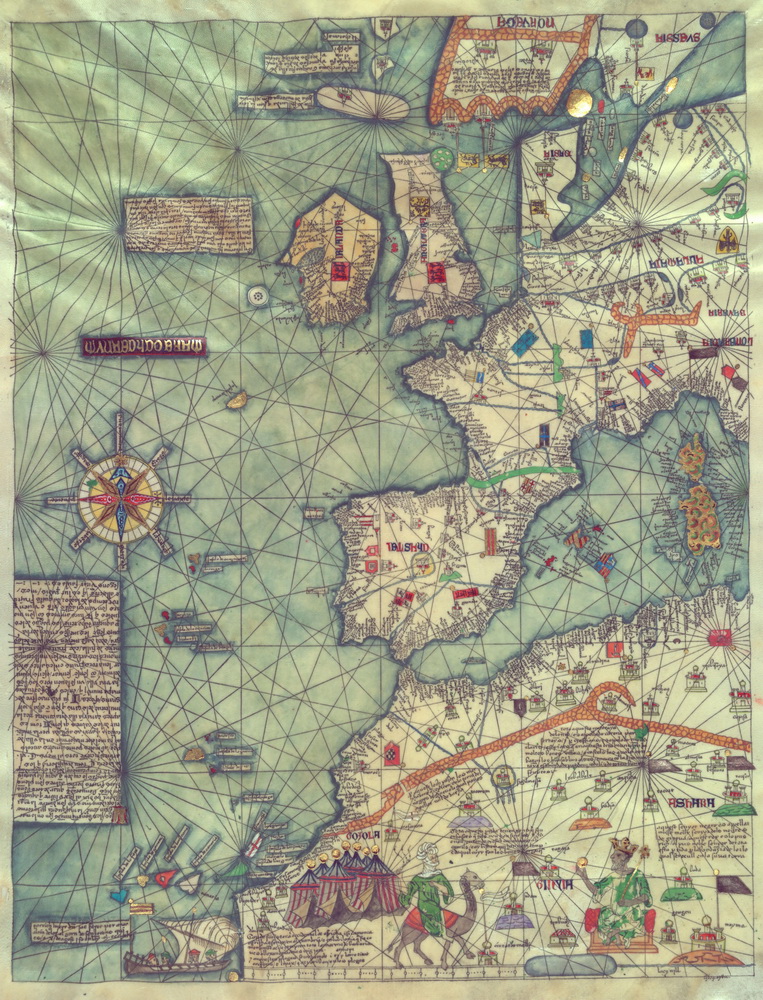

The Majorcan school and the “portolan revolution” (14th–15th c.)

Where and when

Location: Palma (Majorca), Crown of Aragon.

Time: roughly from the 1320s–1330s to the mid‑15th century.

Context: at the crossing of the routes of Genoa, Barcelona, Valencia and the Muslim Maghreb, a workshop tradition of portolan charts arose — practical sea charts for navigation. Within this tradition the Majorcan school stands out with its “hybrid” style: to navigationally precise coastlines it adds inland detail, miniatures, ethnographic and historical‑geographic notes.

What a portolan is — and why it is a “revolution”

Function: not “scholastic” cosmography but a pilot’s working instrument: course, distances, safe coves.

Key features:

A web of rhumbs (16–32 wind directions) radiating from wind roses — the “cobweb” of courses by which a pilot holds direction.

Coastal toponymy: port names written perpendicular to the coastline; major ports in red, secondary ones in black.

Scale/ruling: mileage scales, divisions of “miles” per Mediterranean practice; projection in our sense is not formulated — the chart is empirical, yet along the coasts of the Mediterranean its accuracy is striking for the 14th century.

Practice of sailing: bearing + measured distance (dead reckoning), checking by coastal signs and astronomy.

“The Majorcan style”: where the portolan meets the “world map”

Hybridization: to the precise sea outline they add inland scenes: rivers, cities, mountain systems, rulers’ figures, caravan routes.

Sources of information: travelogues of merchants and envoys, translations from Arabic, Latin chronicles, travellers’ tales.

Illumination: gold, lapis, miniatures of ships and flags, “heads of winds” in the corners.

History of Jewish Cartography: we open this world for you

Language of captions: Catalan, Occitan, Latin (varies), sometimes with Hebrew marginalia in the masters’ workshops.

Workshops and production technology

Materials: parchment (whole skins or joined leaves for large charts/atlases), soot/iron‑gall inks, mineral pigments (azurite/lapis, cinnabar, ochres), sometimes gilding.

Process:

stretching and ruling the base, drawing the rhumb and “wind” networks;

coastline, islands, capes;

toponymy;

decorative elements, flags, miniatures;

mileage scales; as needed — a colophon (signature/date).

Clients: merchants, captains, state patrons (courts of Aragon, Naples, etc.). Prices are high; a chart is both an instrument and a prestige object.

Key figures and charts

Angelino Dulcert (Dalorto), 1339. One of the early works linked with Palma: “Majorcan” traits are already present — densely populated toponymy of the western Mediterranean, attention to the Atlantic. Historians debate whether he is identical with the Genoese Dalorto or a separate master — but his sheet is crucial in the school’s development.

Guillem Soler, c. 1380. A shift toward richer decoration and broader coverage.

Abraham Cresques (†1387) and Jehuda (Jafuda) Cresques. Masters of Palma who worked for the king of Aragon as “masters of maps and compasses.” Their summit is the Catalan Atlas (1375): a six‑leaf giant combining portolan precision of the Mediterranean with a worldly picture of the oikoumene: West Africa with the image of Mansa Musa and gold, caravan routes across the Sahara, India and the Far East from travellers’ accounts, astronomical and calendrical tables. The atlas is the quintessence of the “Majorcan synthesis” of cartography and encyclopedia.

After the pogroms of 1391 Jehuda Cresques was baptized (Jaume Riba). The common hypothesis identifies him with Mestre Jacome, who, according to later reports, was invited to teach cartography in Portugal under Infante Henry; the point remains a matter of scholarly debate.

Mecià de Viladestes, 1413. A chart with a rich Atlantic zone where interest in islands beyond Gibraltar intensifies.

Gabriel de Vallseca, 1430s–1440s. His charts are famed for detailed work on the western Mediterranean and updates on the Atlantic; influential for the next generation of Iberian maps.

Jewish contribution and the “translation of knowledge”

Multilingualism and channels. Jewish masters of Majorca were natural “translators” between the Arabic scientific corpus, the Latin tradition and the practice of Mediterranean pilots.

Data collection. Merchant networks and rabbinic correspondence supplied live information on routes, markets, quarantines, winds; workshops aggregated this into charts.

School of precision. Skill with tables (astronomy/calendar), error‑free copying, experience of sofers and chanceries — all this flowed into cartographic practice: accuracy of coastline and toponymy is not a luxury but a navigational requirement.

What Majorca added compared to Genoa

A hybrid genre: not only “coast for navigation” but also the inland continent with historical and ethnographic inserts (culminating in the Catalan Atlas).

History of Jewish Cartography: we open this world for you

A strong “Atlantic vector”: early interest in the Canary Islands and “islands beyond the strait,” soon taken up by Portuguese cartography.

Iconography and narrative: rulers’ flags, sovereigns, trade scenes, caravans, animals — the map as a story of the world, not only an instrument.

Passing the baton: to the Portuguese and beyond

The pogroms of 1391 and general political turbulence hit Palma’s workshops; some masters and technologies moved to other Iberian centers.

In the 15th century the Majorcan experience merges with the state needs of Portugal and Castile; Iberian planispheres and “secret” Atlantic charts appear.

In early Portuguese traditions one can feel the trace of portolan route‑mathematics and Majorcan interest in the outer world; by the late 15th–early 16th centuries all this will join the Ptolemaic latitude‑longitude frame.

Why this matters in the history of maps

Practical accuracy in the Mediterranean in the 14th century became the base for the oceanic leap of the 15th century.

Majorca showed that a map can be both instrument and encyclopedia: the pilot takes courses and distances, the ruler sees world and resources, the merchant — markets and routes.

Jewish masters played the role of liaison at this node: they glued together languages, tables, routes and stories — into one object we call the portolan chart.

Portuguese navigation and the “cartography of discovery” (late 15th c.) + Spain

Starting conditions: from coast to ocean

Portolan → Ocean. Mediterranean portolans are superb along coasts, but the Atlantic requires more: astronomical navigation, understanding winds/currents, and a new “operational geography.”

The Atlantic conveyor. Island bases (Madeira, Azores, Canaries, Cabo Verde) form the “steps” toward Guinea and beyond. The practice of volta do mar — “return by the sea” — arises, when homeward one sails not “straight,” but via the latitudes of steady winds, using the gyre of trades and westerlies.

Henry the Navigator: a network, not a “university”

Patronage and intelligence. Infante Henry (Henrique) oversaw flotillas from the Algarve (Lagos, Sagres), gathered pilots, translators, roteiros (rutters — textual pilot books), updated notes on currents, reefs, winds. This is a logistics‑and‑intelligence hub, not a school in the academic sense.

Technical processes. Orders for charts and “compasses” (magnetic), standardization of measures, testing helmsmen’s skills. On shore, “logs of the voyage” and draft charts accumulate — raw material for the next generation of planispheres.

Technological leap: how they began to “measure the ocean”

Latitude by the Sun. Noon altitude of the Sun + tables of solar declination → latitude. Instruments: mariner’s astrolabe, quadrant, later the cross‑staff.

Tables and regimentos. Astronomical almanacs and regimentos (instructions) translate astronomy into the step‑by‑step practice of a pilot: “how to take altitude,” “how to apply correction,” “what tolerance to keep in a swell.”

Magnet and courses. The compass gives course, but magnetic declination demands local experience; therefore the “portolan web” remains important, now tied to celestial measurements and time‑keeping.

Institutions and the “secret of charts”

Portugal

Royal warehouses and offices (Casa da Índia / Armazéns) accumulated charts, rutters, “pilot knowledge.” Part of the cartography was kept as a state secret; only a small fraction reached external markets.

Cartographers‑practitioners. Early makers of Portuguese planispheres: the Reinel family (Pedro and Jorge), Lopo Homen, etc. Their sheets combine portolan precision for Africa and the “new shores” of the Atlantic.

Leaks. Famous “leaks” (like the Cantino planisphere, early 16th c.) show the real scale of knowledge accumulated — and how this knowledge instantly becomes a geopolitical resource.

Spain

Casa de la Contratación (Seville, from 1503) — a “navigation factory”: pilot training, instrument standardization, storage of rutters and the master chart matrix (Padrón Real), constantly updated from captains’ reports.

The office of piloto mayor (later chief cosmographers) oversaw chart updates, exams and expeditionary instructions.

State control. Charts and rutters were strategic property of the crown; copying and export were punished.

Columbus (Spain)

Finance and the converso network. Columbus’s first report is addressed to Luis de Santángel (an influential Aragonese treasurer from a converso family), who played a key role in lobbying and financing the 1492 expedition. This links the “politics of discovery” to the Jewish‑Sephardi milieu at court.

Astronomy at work. In the 1504 Caribbean crisis Columbus used a predicted lunar eclipse (from astronomical tables) to pressure local chiefs — a characteristic example of how tabular science turned into navigational “psychology” of control.

Vasco da Gama (Portugal)

Latitude by the Sun — “threshold to the ocean.” The breakthrough came from Abraham Zacuto’s Almanach Perpetuum (solar declination tables) and the practice of the mariner’s astrolabe — this made measuring latitude feasible in the tropics, where the Pole Star is a poor guide. The translation and edition of the tables in Portugal was carried out by José (João) Vizinho; the crown even sent him “into the field” (Guinea) to test solar altitudes.

Effect on maps. When latitude became routine, Iberian planispheres confidently “set” the coasts of Africa and India — as we see in early works of the Reinel family and Lopo Homen.

Magellan (Spain, in Castilian service)

The “machine of charts.” By the time of Magellan’s expedition the Casa de la Contratación (Seville) was operating: pilot training, instrument standards and the Padrón Real — the “secret matrix” of Spanish mapping, continuously updated by ship logs. The first circumnavigation ends under Elcano, fixing Spain’s Atlantic–Indian routing system.

“The Jewish link”

Knowledge → instrument. Zacuto (tables) + Vizinho (translation/field tests) = applied astronomy turned into the craft of the pilot; without it, ocean sailing on the “portolan cobweb” would not have worked.

Channels and capital. Sephardi and converso elites at court (ex. Santángel) link the idea of expeditions to money and crown bureaucracy — this too is “part of cartography,” because it determines what data enter the “state chart” and which routes get continuations.

From workshops to institutions. Portuguese cartographers (the Reinels, Homen) and Spanish institutions (Casa, Padrón Real, the post of Piloto Mayor) show how knowledge from the Jewish‑Arabic scientific tradition became embedded in the state system of navigation and secret charts.

Political‑cartographic frame: Tordesillas and the “partition of the world”

Demarcation line (1494). Portugal and Spain agree on dividing spheres of influence by an Atlantic meridian. This turns cartography into an instrument of international law: where to draw the line is not a draughtsman’s question but a colonial one.

Imperial logistics. Colonies/factories mean charts, rutters, tables, stores and repair in anchor ports. Any new cape, bank or current immediately enters the crown’s cartographic memory.

People and instruments: who made the leap possible

Abraham Zacuto — royal astronomer of Portugal; his solar declination tables and practical method of latitude became the everyday tool of ocean voyages.

Martin Behaim — the epoch’s “spherical” mindset: his globe (1492) is still naive about the oceans but sets a three‑dimensional frame for thought and commissions.

The Reinels, Lopo Homen, António de Holanda — the “face” of the Portuguese planisphere school of the early 16th century; the fact that their charts already calmly show the coasts of Brazil, Guinea and India is a direct result of the accumulation of “secret” rutters in the 15th century.

Spanish line: Juan de la Cosa draws the first general map with the New World (1500); later Seville cosmographers consolidate the data in the Padrón Real; printed navigation treatises (Pedro de Medina, Martín Cortés) translate the pilot’s craft into a teaching norm.

What exactly changes on the map

From the “web of winds” to the planisphere. The portolan rhumb web remains, but the “world map” gains an Atlantic and Indian ramp: equator, tropics, meridian guides appear on sheets, and textual inserts on currents and “Trades run like this.”

Colonial semiotics. Maps display flags, padrões, captions “such‑and‑such land discovered in year so‑and‑so.” The map records title and the “history of discovery,” not only pilotage.

Jewish / converso contribution in the Iberian system

Tables and translation. Astronomical tables, translations and adaptation of Arabic applied astronomy are the working tool of navigation; here the role of scholars of Jewish origin and their students is noticeable.

“Escriva/Escriba.” Notarial and scribal dynasties in Iberia handle maritime business documentation: contracts, translations, rutters. The professional line of scribes (sofers/escribas) carries to sea the same culture of precision and checking as in canonical texts.

Later bridge to navigation science. In the 16th century Pedro Nunes (from a New Christian family) gives the loxodrome and errors of charts a mathematical treatment, laying a foundation for the next century’s navigation theory.

Spain and Portugal as “cartographic powers”

Portugal builds an oceanic “pipeline” to India and Southeast Asia, and then to Brazil; its charts are initially closed, but their style and solutions spread rapidly across Europe.

Spain turns Seville into the “capital of the ocean”: all “Indies” ships pass through the Casa de la Contratación, where their logs are turned into updates to the Padrón Real.

Both crowns understand: a chart is as strategic a weapon as a fleet. Without centralized cartography one cannot maintain routes or argue “lines” with neighbors.

Brief conclusion

The end of the 15th century is the moment when Mediterranean pilotage merges with astronomy and state record‑keeping, and the chart turns from a “pilot’s hide” into an instrument of empire. Portuguese practice (latitude, volta do mar, closed planispheres) and Spanish institutionalization (Seville, Padrón Real) together set the standard of the geography of discovery for a century ahead.

Amsterdam (Sephardi) print and engraving (17th c.) → the German school (J. G. Schreiber) → Britain as a maritime superpower

After the expulsions: why Amsterdam

After 1492–1497 (Spain/Portugal) part of Sephardim moved to the Ottoman Empire, to Livorno/Hamburg — and to Amsterdam. Three factors coincided there:

Toleration and capital: the city readily accepted merchants and printers, extended credit, attracted specialists in Hebrew, Ladino, Portuguese.

A de facto maritime republic: global trade demands fresh charts, portolans, atlases, town plans — and creates paying demand.

Printing technologies: copper‑plate engraving, good pigments, crisp typography. Amsterdam becomes a “factory” of both books and cartographic products.

In this ecosystem Sephardim occupy niches of printers, engravers, translators, booksellers — and suppliers of geographic information from their international network.

The Sephardi map and sheet as a “business model”

Bookmaking as infrastructure: Jewish presses and workshops issue Bibles, commentaries — and in parallel master copper‑plate engraving, Hebrew/Latin typesetting, book illustration. The same techniques flow into maps and plans.

Monuments and iconography: the Amsterdam tradition of “Jewish maps of the Holy Land” crystallizes by the late 17th century; stable motifs — tribal allotments, the Exodus route, Temple plans (influence of the scholar‑“Templist” Jacob Judah Leon Templo). This forms its own visual norm for Judaica and for “oriental” maps in general.

Role of translation and mediation: Sephardi merchants and scholars bring texts and reports in several languages into workshops; captions, “historico‑geographic” inserts and updates for Dutch houses (Blaeu, Janssonius, Hondius, etc.) grow from this.

Key figures and practices

Abraham bar‑Jacob — an engraver‑convert of the Amsterdam school: the Jewish map of Eretz‑Israel in late‑17th‑century editions became canonical and spread across Europe in dozens of reissues; around it a whole “genre” formed for communities, schools and charitable editions.

Jacob Judah Leon Templo — plans/etchings of the Temple and Tabernacle, large models and accompanying schemes. His visual language “codes” Jerusalem and the Holy Land for many later engravings and maps.

Menasseh ben Israel and other publishers — a typographic base (types, ornament, paper) on which it is easy to issue maps (inserts, appendices, separate sheets).

Result: Amsterdam makes the map a mass printed product, and the Sephardi network supplies it with multilingual captions and storyline (Holy Land, the East, “histories of countries”).

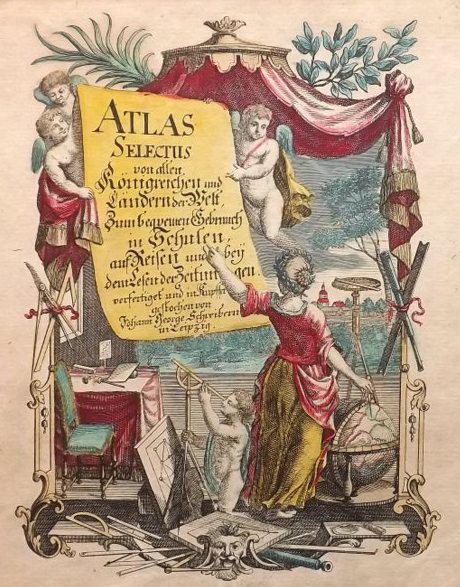

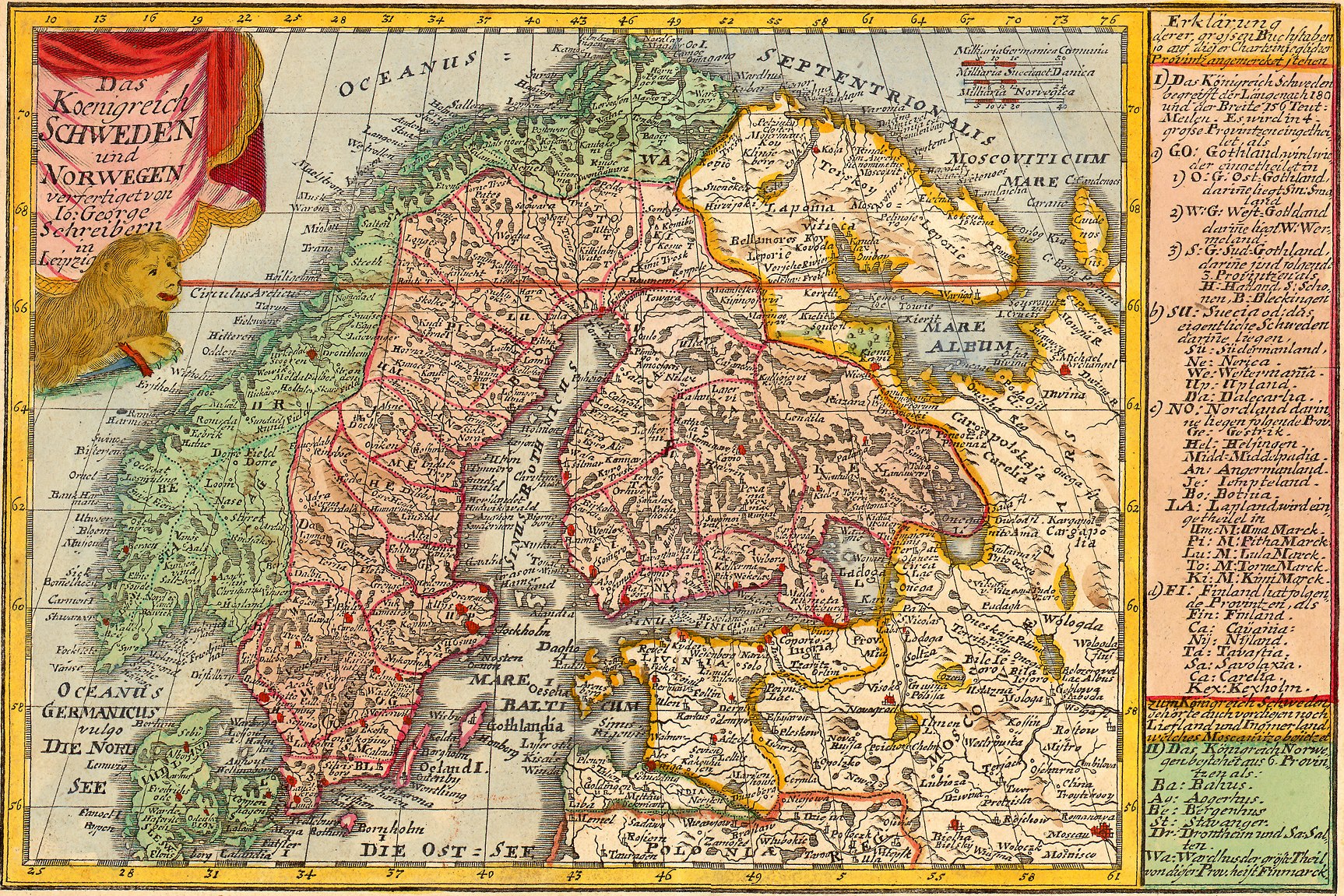

From Amsterdam to the German map: Johann Georg Schreiber and “middle” Europe

In the late 17th—early 18th centuries the Dutch style (crisp outline, cartouche, graticule of meridians/parallels, neat type) spreads across Europe. In the German lands:

Leipzig, Nuremberg, Augsburg — centers of the book and engraving trade. Here Dutch models are actively reprinted, compiled, simplified for the average buyer.

Johann Georg Schreiber (1676–1750) — a typical representative of this wave: a publisher‑engraver making pocket atlases, wall sheets, town plans, “teaching” maps with clear lettering and dense micro‑detail. His output is the democratization of maps: cheaper, more accessible, with good readability.

Trade fairs and catalogues turn maps into a broad commodity: from princes’ cabinets to teachers’ shops, innkeepers, merchants’ counting‑houses. Thus a “daily” geography of the German‑speaking world takes shape, no longer elitist.

Britain: from importing Dutch tricks — to its own hydrography

By the late 17th century the center of power in the Atlantic shifts:

London adopts the Amsterdam idea of the “map‑as‑commodity”: “map shops” and the first English sea collections appear; in parallel domestic cartography matures (road atlases, town plans).

Practice of navigation makes a leap: the English systematize coastal pilotage, winds and currents, begin to collect data on magnetic declination and on “rules” of seasonal routes. The map becomes a weapon alongside the fleet.

Imperial organization: the crown and companies (e.g., the East India Company) develop the habit of collecting, standardizing and storing: captains’ logs → instructions → new editions of charts. Regulations for pilot training appear; basic pilots for theaters of sailing.

Change of hegemon: Spain, which kept charts “under the bushel” and relied on closed state archives, loses pace; Britain, relying on the print market + fleet + science, forms its own cartographic “ecosystem,” which in the 18th century grows into a developed state hydrographic service and sets the standard for global sea charts.

What links the three lines — Amsterdam → Germany → Britain

Technology of copper engraving and book logistics: a common craft language, easily portable between cities and countries.

Networks of knowledge: Sephardi go‑betweens and publishers in Amsterdam, book fairs and guilds in German centers, maritime corporations in London — all this is a conveyor of updates.

From the “show map” to the “tool map”: the decorative Amsterdam sheet gives a “cartographic grammar”; the German school makes it mass‑market; the British take it to ultimate practicality at sea.

Conclusion: Amsterdam of the 17th century is a “launch pad” of printed cartography where the Sephardi diaspora connects languages, storylines and craft. German masters turn this style into an accessible “teaching and trade” standard, and Britain — into a system of navigation charts serving the rise of the empire on ocean communications.

After the expulsions (1492–1497): the New World, Tortuga, and “Jewish pirates” of the Caribbean

Waves of resettlement and the first anchor communities

After the expulsions from Castile and Portugal, Sephardim settled in the Ottoman Empire, North Africa and the Netherlands, and in the 17th century — in Dutch Brazil (Recife). There in 1636 a community and the synagogue Kahal Zur Israel appeared — one of the first documented Jewish houses of prayer in the Americas. After the fall of the Dutch regime in 1654, residents of Recife dispersed across the Caribbean and to New Netherland (New Amsterdam): a group of 23 Sephardim arrived in September 1654, laying the foundation of the American Jewish community.

The Caribbean map: where the diaspora took root

Curaçao. The congregation Mikvé Israel — from 1651; the present synagogue Mikvé Israel–Emanuel was dedicated in 1732 and is considered the oldest in continuous use in the Americas.

Barbados. Nidhe Israel in Bridgetown: the community formed soon after 1628; the synagogue is attested from 1654 (the complex today is a UNESCO site).

Jamaica. After the English conquest of the island (1655) Jews settled in Port Royal (then — in Spanish Town and Kingston); early synagogues are documented in 18th‑century sources.

These nodes became a logistics network of trade, credit, cargo insurance — and sources of information for European cartographers and pilots (rutters).

Tortuga: what is known about Jewish presence and “synagogues of Tortuga”

Tortuga (Île de la Tortue, Hispaniola) is a famous base of 17th‑century buccaneers. Reliable evidence exists for a small Jewish presence in the colony of Saint‑Domingue (including Tortuga), but there is no documentary proof of a synagogue on Tortuga: scholars stress that because the community was tiny a prayer house was not built there. On the mainland of Haiti (the town of Jérémie) archaeologists reported remains of an early synagogue — but that is not Tortuga.

“Jewish pirates” of the Caribbean: what the term hides

It is more correct to speak of privateers of Jewish origin acting under Dutch and English commissions against Spain.

Moses (Moisés) Cohen Henriques is the firmest case: he took part in the capture of the Spanish Silver Fleet in Matanzas Bay (Cuba), 1628, together with Admiral Piet Hein (WIC). The event is well attested in historical literature.

After the Dutch–Spanish wars some such privateers settled in the Atlantic colonies of the Netherlands and England (Jamaica, Curaçao), supporting a symbiosis of privateering and trade: merchants supplied, bought prize goods, gave credit — and privateers “solved problems” at sea. For Jamaica the mutual links of pirates and Jewish merchants in the colony’s economy have been shown.

Recife and the “pirate thread.” After his privateering career Cohen Henriques is linked with the Dutch Brazil community; local histories and museum texts note his participation (with his brother) in the formation of Kahal Zur Israel — showing how a “maritime” biography entered the institutional life of the diaspora.

Individual figures like the “rabbi‑buccaneer” or “pirates of Jamaica by epitaphs” occur in popular literature but are weakly documented; professional historians urge distinguishing legend from archive.

Why this matters for mapping and navigation

Diaspora networks after 1654 gave the Anglo‑Dutch world port infrastructure, translators, notarial offices and credit — the things on which navigation rested and by which rutters/charts were updated.

Caribbean communities (Curaçao, Barbados, Jamaica) became nodes of transmission: a barometer of prices, quarantines, depths, winds, safe harbors — all that flowed into hydrographic instructions and cartography.

Figures of the history:

— Abraham bar‑Jacob — Jewish map of the Holy Land.

— Abraham bar Hiyya — geometry/trigonometry for maps.

— Abraham Zacuto — declination tables, mariner’s astrolabe.

— Abraham Cresques — Catalan Atlas, Majorcan portolans.

— Amiran, David — editor of the Atlas of Israel, geographer.

— Angelino Dulcert (Dalorto) — early Palma portolan, 1339.

— António de Holanda — courtly atlases, Portuguese illumination.

— Behaim, Martin — 1492 globe, early cosmography.

— Blaeu, Willem Janszoon — Amsterdam atlases/maps, 17th c.

— Blaeu, Joan — large atlases, Dutch school.

— Vallseca, Gabriel de — Majorcan portolans, 15th c.

— Viladestes, Mecià de — 1413 portolan, Atlantic islands.

— Vizinho, João (José) — translated/tested Zacuto’s tables.

— Vilnay, Ze’ev — Israeli geographer, map popularizer.

— Gil, Moshe — Radhanites, Geniza documents, historiography.

— Goitein, Shlomo Dov — Cairo Geniza, Mediterranean trade networks.

— Da Gama, Vasco — route to India, astronomical navigation.

— De la Cosa, Juan — first map with America, 1500.

— De Medina, Pedro — Spanish navigation treatises, manuals.

— Jansson, Jan (Janssonius) — Dutch atlases, Blaeu rival.

— Zacuto, Abraham — see above (tables, astrolabe).

— Ibn Athari, Mashallah — astrolabe treatises, Baghdad.

— Ibn Ya‘qub al‑Tartushi, Ibrahim — traveller; described Central Europe.

— Jehuda (Jafuda) Cresques / Jaume Riba — Majorcan master; co‑author of the 1375 atlas.

— Ishtori ha‑Parchi — geography of Eretz Israel, 14th c.

— Columbus, Christopher — 1492+ expeditions, Caribbean, Atlantic.

— Cortés de Albacar, Martín — navigation theory, Spain, 16th c.

— Lopo Homen — Portuguese planispheres, court cartography.

— Luis de Santángel — treasurer; lobbied Columbus’s voyage.

— Magellan, Ferdinand — circumnavigation; Strait of Magellan.

— Menasseh ben Israel — publisher; Amsterdam Hebraica/maps.

— Moses Cohen Henriques — Jewish privateer; capture of the Silver Fleet.

— Nunes, Pedro (Nonius) — loxodrome; Portuguese navigation math.

— Pallache, Samuel — merchant‑diplomat; Morocco–Netherlands privateer.

— Pedro Reinel — early Portuguese planispheres; Atlantic.

— Piet Hein — WIC admiral; Matanzas 1628.

— Prince Henry the Navigator — patron of expeditions; rutter network.

— Reinel, Jorge — cartographer; Pedro’s son; pilot training.

— Saadia Gaon — calendar; mathematical culture; responsa.

— Santángel, Luis de — see above (Columbus financing).

— Sinan Reis — Ottoman corsair; debated origins.

— Soler, Guillem — Majorcan portolans, 14th c.

— Templo, Jacob Judah Leon — Temple plans; Jerusalem iconography.

— Hondius, Jodocus — Dutch atlases; engraver‑cartographer.

— Khordadbeh, Ibn — Book of Roads and Kingdoms; Radhanites.

— Schwarz, Yosef (Joseph) — maps/geography of Eretz Israel, 19th c.

— Schreiber, Johann Georg — German atlases; mass‑market cartography.

— Elcano, Juan Sebastián — completed Magellan’s circumnavigation.