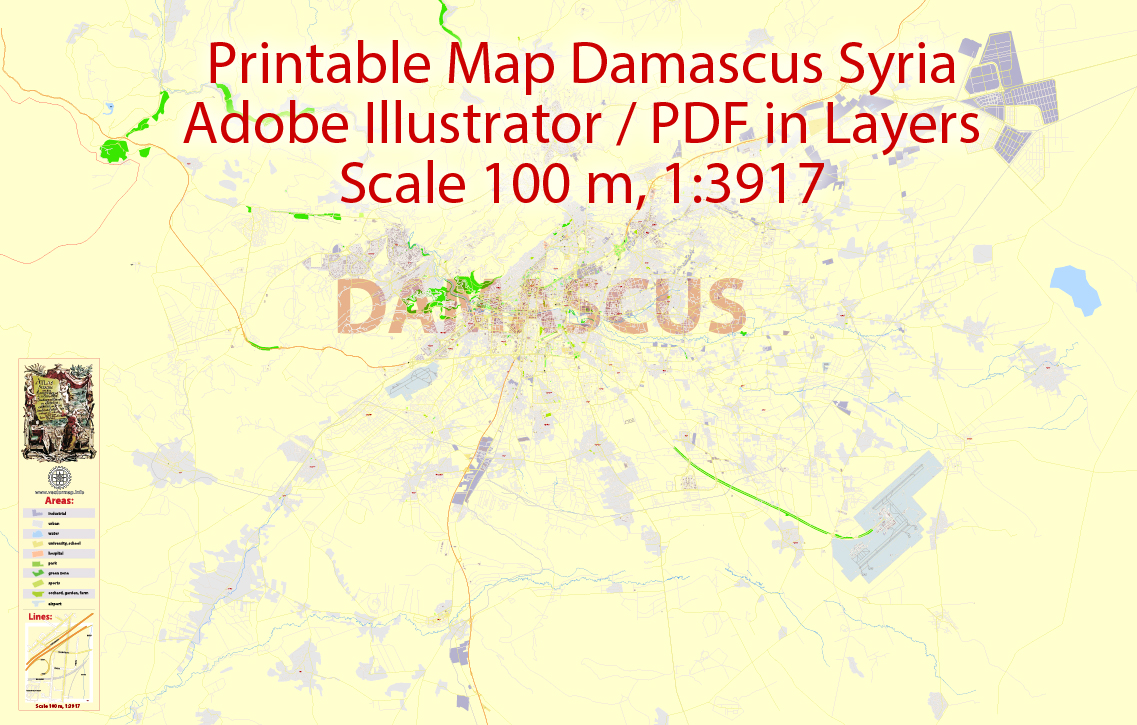

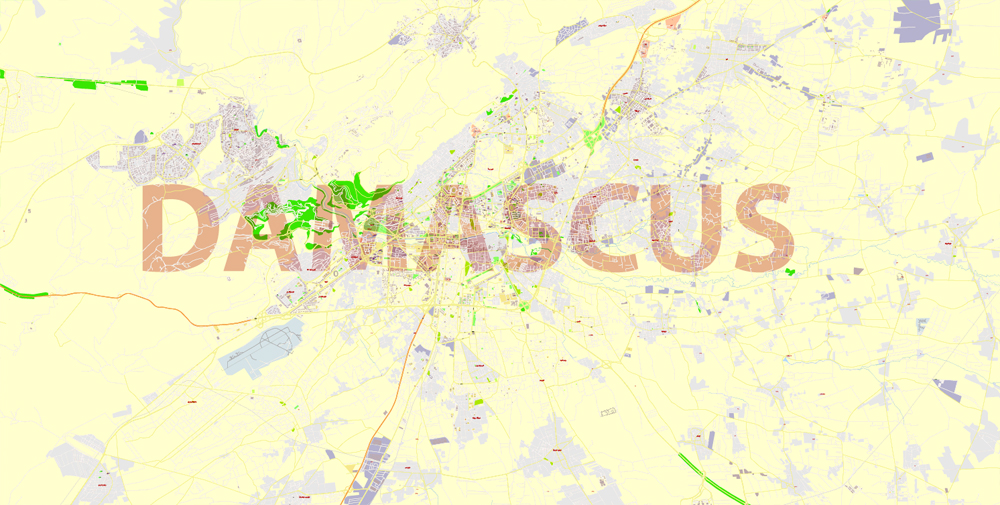

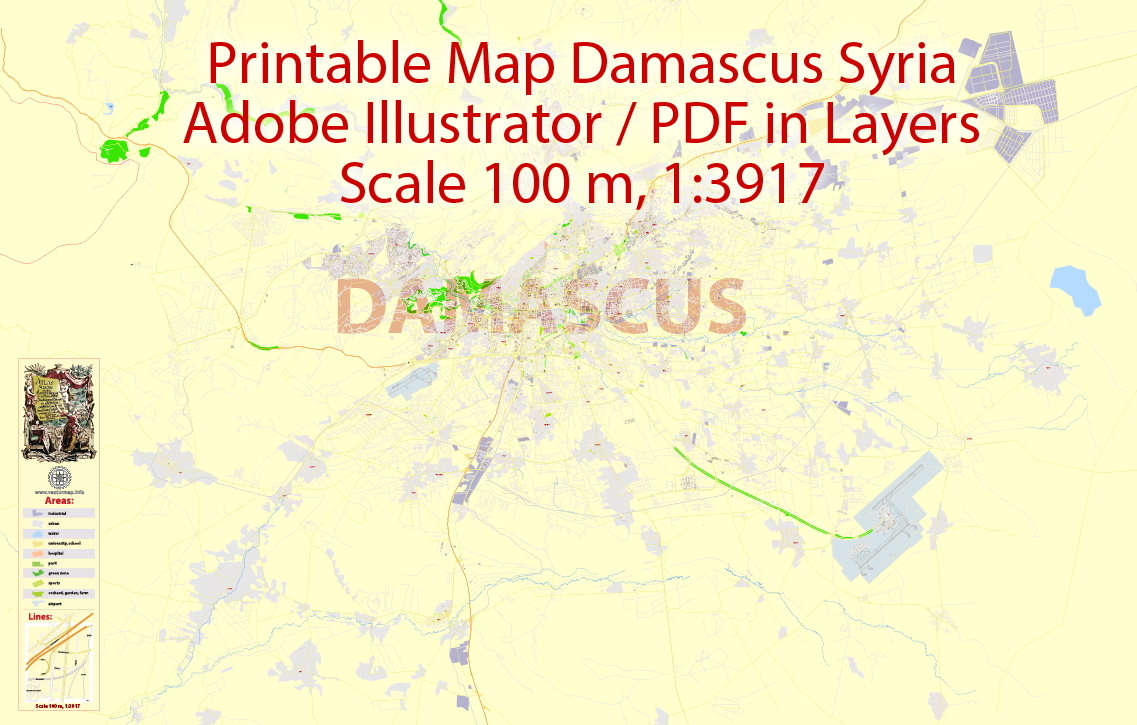

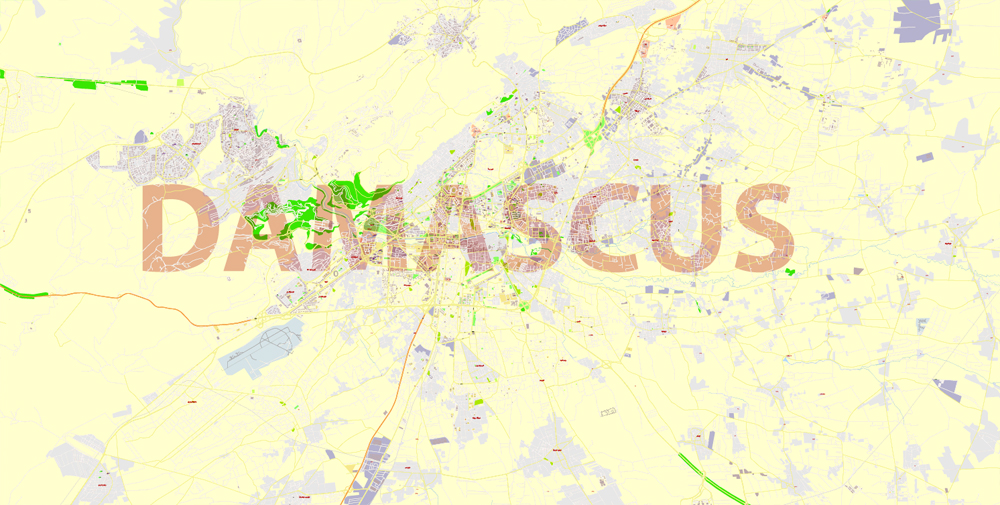

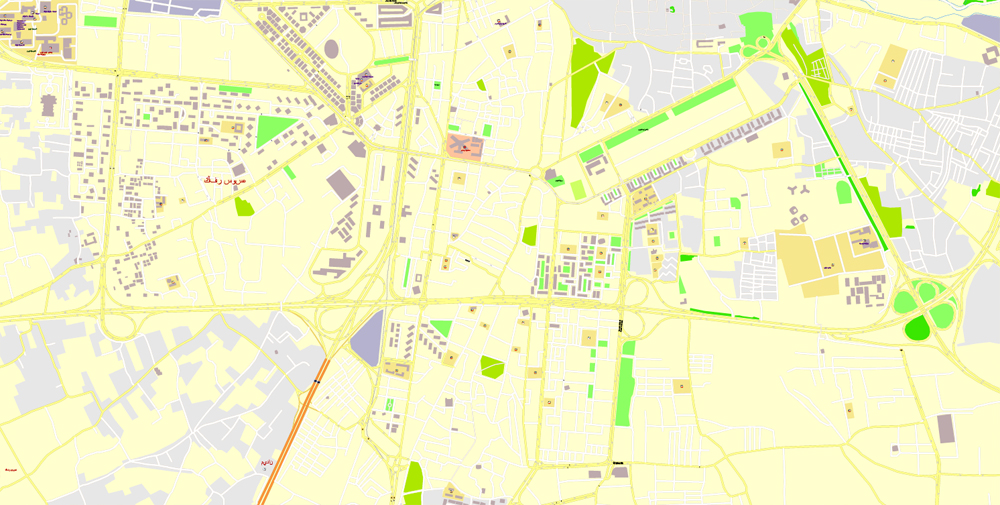

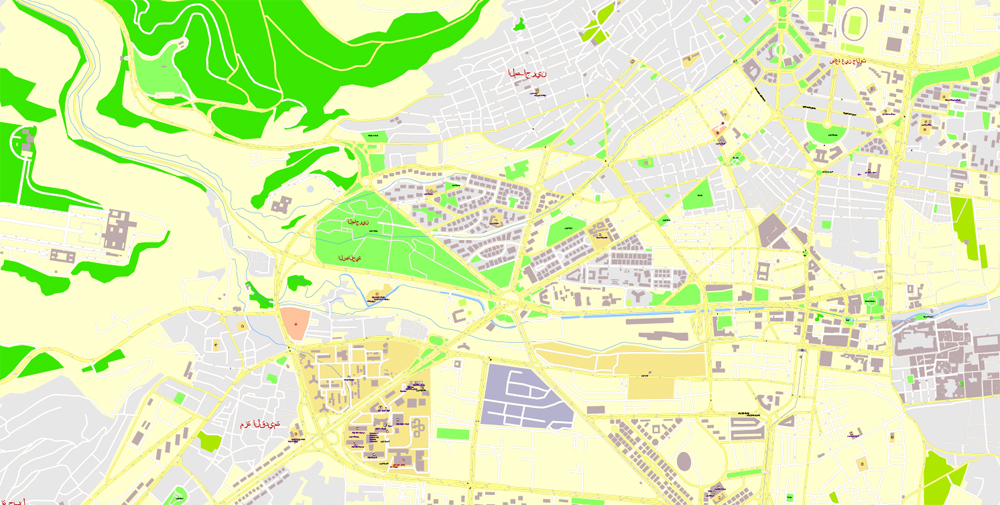

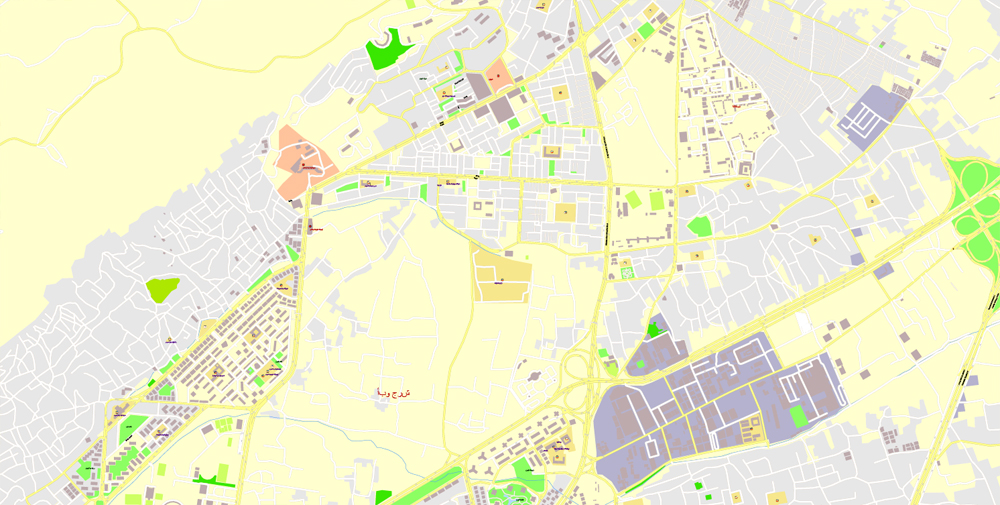

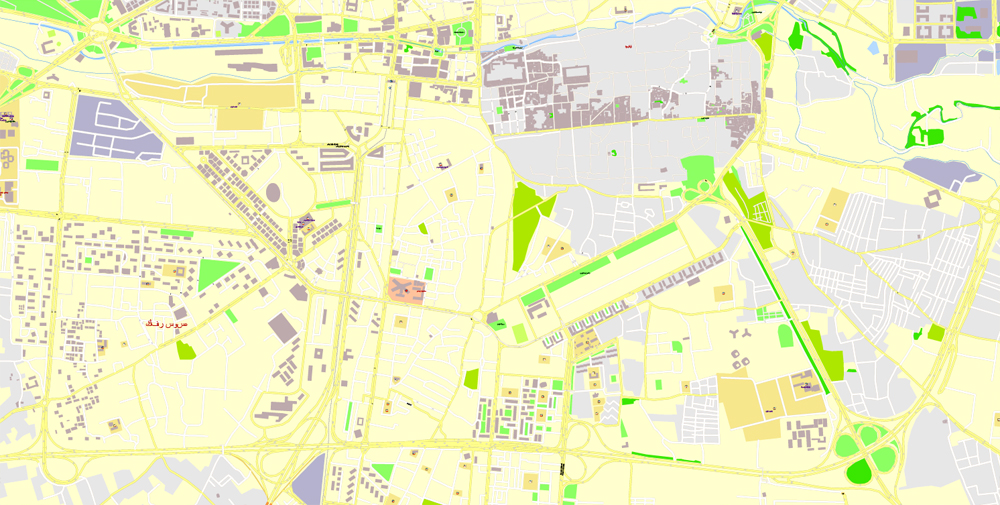

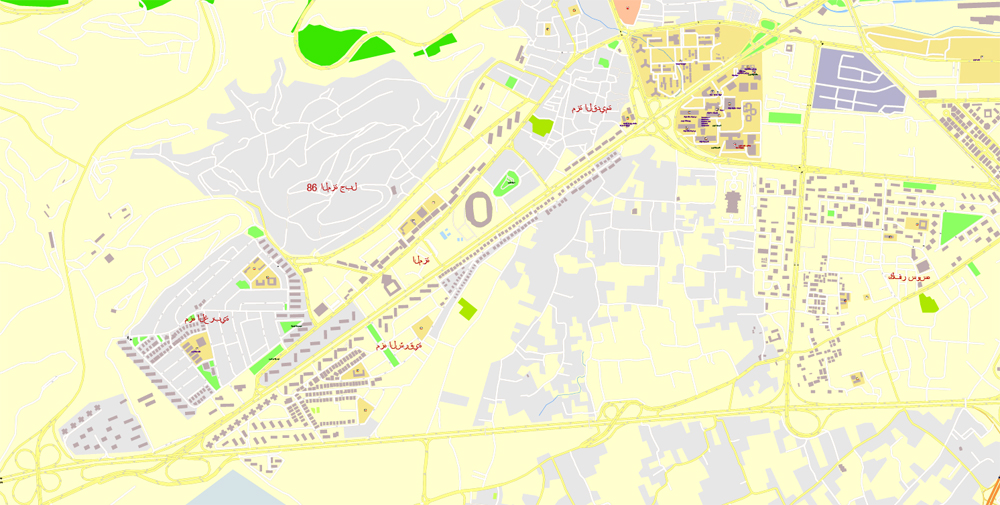

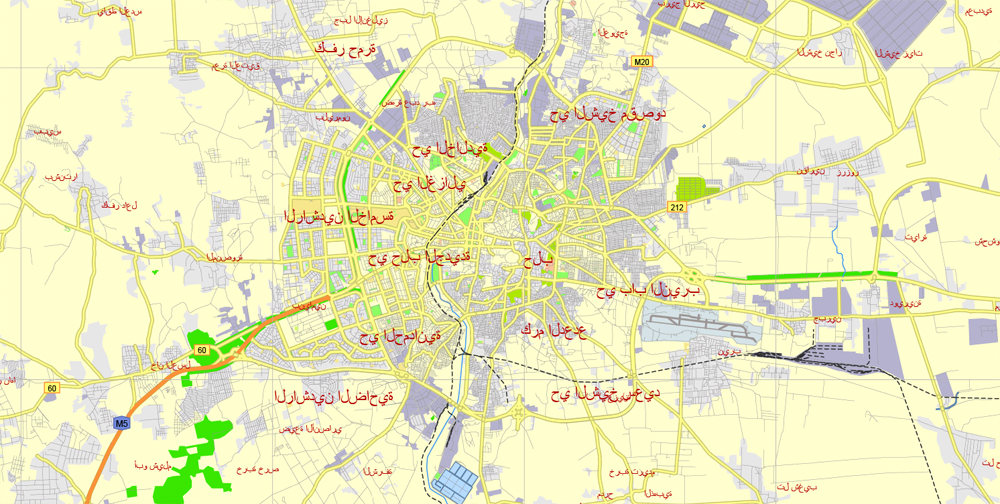

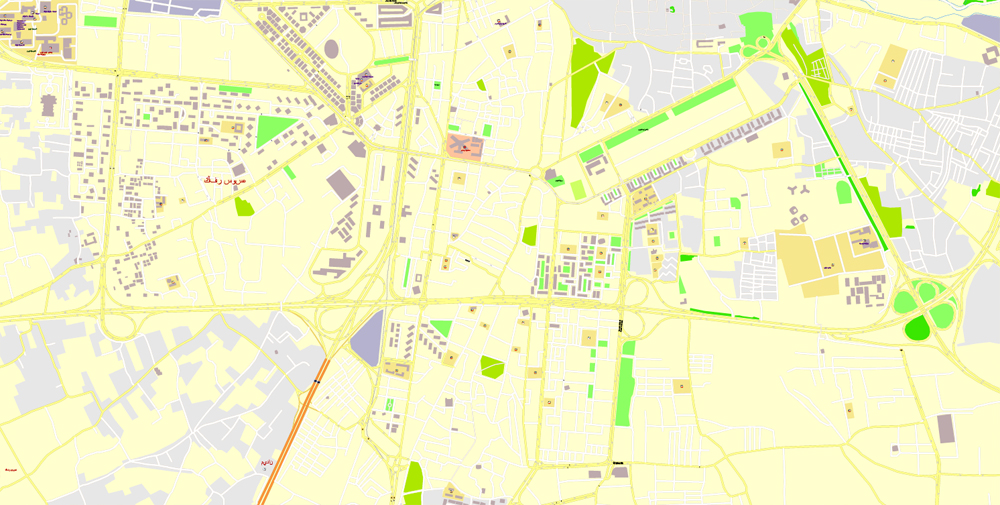

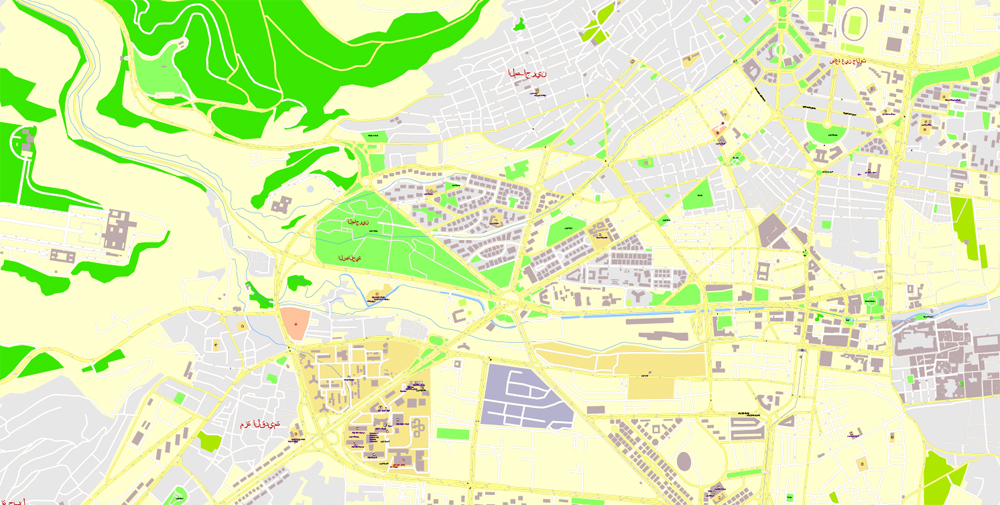

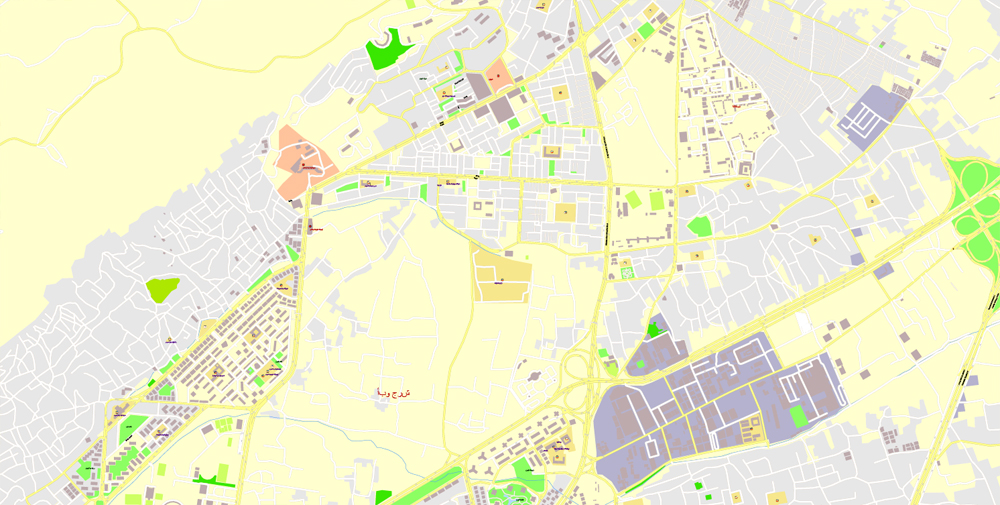

Urban plan Damascus Syria: Digital Cartography

Related Video "Urban plan Damascus Syria":

Gallery of Images "Urban plan Damascus Syria":

The Urban Development of Damascus: City Maps for Printing.

Urban plan Damascus Syria: Fully Editable Vector Maps for History and Geographic Research

DAMASCUS is one of the oldest cities in the Middle East and the world, currently the capital of the Syrian Arab Republic, the modern residence of the Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch.

Geographical and economic situation.

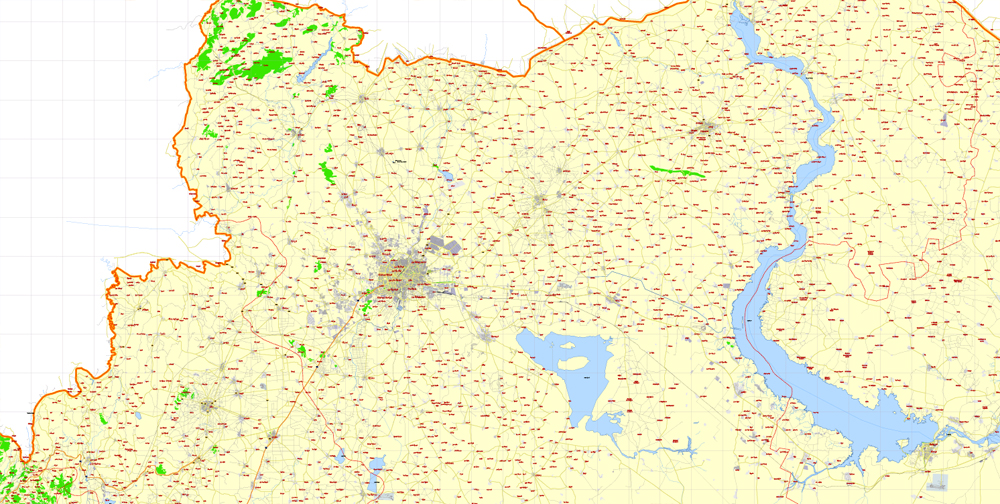

Damascus is located east of Mount Hermon (modern-day El-Sheikh (Hermon)), at the foot of the eastern slope of the Anti-Lebanon ridge on the border of the Syrian desert, along the banks of the Avana River (modern Barada), the only permanent source of water in the region. Thanks to this, the Damascus region has always been one of the richest agricultural regions in the Middle East. Wine from Damascus, especially from Khelbon (north of Damascus), was famous throughout the Middle East (Ezek. 27. 18; Strabo. Geogr. XV 3. 22). Since ancient times, caravan routes from north to south have passed through the territory of Damascus.

The oldest evidence.

Damascus was first mentioned in the list of Syro-Palestinian cities discovered on the walls of the temple of Amun in Karnak, the rulers of which were captured by Pharaoh Thutmose III (about 1504-1450 BC) after the battle of Megiddo around 1482 BC. It is also found on a statue found in the tomb of Amenhotep III (about 1417-1379 BC), which lists several cities and states that were subordinate to Egypt (or in friendly relations with it), as well as in the Amarna letters and on a tablet found in Kamid-el-Loz (Kumidi) (XIV century BC). According to these sources, Damascus in the XV-XIII centuries BC was in the sphere of the political influence of Egypt. The land of Apum, within which Damascus was located, was at the center of the confrontation between Egypt, the Hittite state, and Mitanni for dominance in Syria. The Hittites' struggle with Egypt for Damascus and Apium during the reign of Amenhotep IV is described in 4 Amarna letters (EA. 53, 107, 189, 197). Damascus is mentioned twice in the book of Genesis in connection with the narratives of the patriarchs (Gen. 14:14-15; 15:2). However, the attribution of these mentions to a specific historical epoch is the subject of scientific controversy.

The Aramaic kingdom of Damascus.

In the X-VIII centuries BC, Damascus was the capital of one of the Aramean states - the Kingdom of Damascus (Aram-Damascus; Heb. - 1 Par 18. 5-6; cf.: Is 7. 8). The first mention of the kingdom of Damascus in written sources is found in the story of King David's war with the Aramaic kingdom of Suva (Aram-Tsoba) (2 Kings 8; 1 Par 18), which became the dominant force in Southern Syria in the early years of King David's reign. He defeated the Suva king Adraazar in 2 battles (2 Kings 8. 3-8; 10. 15-19). According to 2 Kings 8, after the battle with Adraazar, David defeated the army of the Arameans from Damascus and incorporated the city into his kingdom. Damascus remained under the rule of the Israelites until the reign of King Solomon, when Razon, the son of Eliad, a former servant of Adraazar, gathered an army of rebels, captured Damascus and proclaimed himself king (3 Kings 11:23-25). Razon soon became an opponent of Israel in alliance with the Edomites (3 Kings 11:25). Solomon was unable to regain control of Damascus, around which other Aramaic states were united.

The influence of Damascus increased under Razon's successor, Taurimon. In the IX-VII centuries BC, the Aramaic kingdom of Damascus was the main opponent of the Northern Kingdom. Under the leadership of Ben-Hadad (about 900 BC), Damascus attacked Israel after concluding an alliance with the Jewish king Asa and plundered most of its northern territory (3 Kings 15:16-22 = 2 Pairs. 16. 1-6). The Israelite king Ahab managed to defeat the troops of Benadad at Afek (3 Kings 20. 26 sl.), but he himself, in connection with the prophecy, left alive, having concluded a treaty with him (3 Kings 20. 35-42). The coalition of States created by this treaty was directed against Assyria. According to the annals of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, at the Battle of Karkar (about 853 BC) Assyria was opposed by a military coalition of 12 states, headed by King Adadidri of Damascus. One of the participants in this battle was the Israeli king Ahab (ANET. 278-279). Many researchers identified Venadad I with Adadidri, believing that the battle of Karkar took place in the period between the battles described in 3 Kings 20 and 22. According to other scholars, the narrative of the Aramean wars with Israel originally did not contain the name of the king of Israel and was mistakenly attributed to the era of the reign of King Ahab (see: Pitard. Damascus. P. 6). Perhaps it referred to the battles at the beginning of the VIII century between the Israelite king Joash (or Jochaz) and Benadad III, the son of the Aramean king Hazael (cf.: 4 Kings 13: 14-19, 24-25).

The hegemony of the Kingdom of Damascus in southern Syria and Palestine continued under Azael, who seized the throne around 842 BC (4 Kings 8:7-15). Having been initially weakened by the confrontation with Shalmaneser III in 841 and 838 (and probably also in 837), Hazael subsequently strengthened his power and began to pursue a policy of creating an empire. By the time of his death, the Aramaic kingdom of Damascus controlled most of the territory of Southern Syria and Palestine, including Israel (areas west and east of the Jordan), the Kingdom of Judea, Philistia, and probably the state in the Jordan (4 Kings 10:32-33; 12. 17-18). The prophet Elijah received a command from the Lord to anoint Hazael to reign in Syria (3 Kings 19:15), which, apparently, only the prophet Elisha could fulfill (4 Kings 8:7-15).

Under the successor of Hazael, his son Venadad III (the end of the IX century BC), the Aramean empire collapsed. Around 796, the Assyrian king Adadnirari III besieged Damascus and forced Venadad III to pay a large tribute. The Israelite king Joash defeated Benhadad in 3 battles (4 Kings 13:24-25), managing to regain the cities previously captured by the Arameans (4 Kings 10:32). It is known from extra-biblical sources that Damascus was also defeated in the conflict with the ruler of the united lands of Hamat and Luash Zakir (ANET. 655-656).

In the 1st half of the VIII century BC, the Aramaic kingdom of Damascus was in decline and in fact became a vassal of Israel during the reign of Jeroboam II (circa 782-748; 4 Kings 14:25, 28). However, Damascus played a leading role in the anti-Assyrian coalition around 735, along with Tyre, Israel, etc. The Damascus king Retsin and the Israeli king Pekah tried to enter into an alliance with the Jewish king Ahaz, but his refusal (4 Kings 15. 36; 16. 5) led to the invasion of these kings in Judea and the siege of Jerusalem. Then Ahaz turned to Assyria for help. Tiglath-Pileser III invaded Syria around 733-732 and destroyed almost all the cities in the Aramaic kingdom (according to his annals, 591 cities in 16 districts of Aram - ANET. 283). He also killed Retsin and resettled the inhabitants of Damascus to Cyrus (4 Kings 16. 9; Am 1. 5; 9. 7). The kingdom of Damascus was divided into regions and became part of the Assyrian Empire. From that time on, Damascus turned into the capital of the Assyrian province (also called Damascus), which became the fulfillment of the prophecies about the judgment on Damascus (Is 17:1, 3; Jer 49:23-27). In Damascus, there was a temple of the main deity of the Aramean pantheon - the god of thunder Hadad (see mention in 4 Kings 5. 18 of the sanctuary "House of Rimmon" in Damascus), which was probably located on the site of the Umayyad mosque in the current Old City.

Damascus remained under Assyrian rule until the end of the 7th century. In 720, Damascus, along with other cities, joined Hamat, the only independent Syrian kingdom, rebelling against Assyria. However, Sargon II defeated the rebel forces at Karkar. Hamat was incorporated into the empire, and in 717 exiles from a number of cities were resettled in Damascus. The ruler of Damascus is mentioned in the list of the highest Assyrian officials in 694 and 650. During the military campaign against the Arabian tribes, Ashurbanipal used Damascus as a springboard before the battle of 640. Damascus probably regained its independence at the same time as the collapse of the Assyrian Empire. Like most states in Southern Syria and Palestine, Damascus fell under the rule of Babylonia in 604, and after 539 became part of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, retaining, however, the position of one of the most significant and developed centers of the region (Strabo. Geogr. XVI 2. 20).

Damascus in the era of Hellenism and the Roman Empire.

In 333 BC, Parmenion, one of the generals of Alexander the Great, occupied the city without a fight. Since that time, Damascus has remained under the influence of Western cultures for about 1000 years. During the Hellenistic era, the city was mainly part of the Middle Eastern kingdom of the Seleucids, although it was repeatedly disputed by the Egyptian Ptolemaic kingdom. Greek colonists were settled in Damascus, the city received the status of a polis and enjoyed the rights of internal autonomy. To the north of the old Aramaic city, closer to the river floodplain, there were quarters of Hellenistic development. The exact date of the construction of the "new" Hellenistic city is unknown, presumably, its origin dates back to 200-120 BC, when the center of the Seleucid empire shifted from Northern Syria to Southern Syria and caravan trade resumed through the Syrian desert along the route Dura-Europos-Palmyra-Damascus. In 111 BC, King Antiochus IX moved his capital from Antioch to Damascus. Also, under kings Demetrius III Euker (95-88) and Antiochus XII Dionysus (87-84), Damascus was the capital of the already disintegrating Seleucid empire. In 84 BC. in a battle with the Nabataean king Aretha III, Antiochus was killed, and, apparently, because of the threat from the Itureans, the inhabitants of Damascus invited Aretha as a ruler (Ios. Flav. Antiq. XIII 15. 1-2; De bell. I 4. 7-8). Nabataean settlers formed a new quarter of Damascus to the east of the Hellenistic city. In 72, the city was briefly occupied by the troops of the Armenian king Tigran II the Great, who entered the war with Rome. After his defeat in 69, Damascus became independent.

In 66 BC Damascus was captured by the generals of Gnaeus Pompey - Lollius and Metellus (Ios. Flav. Antiq. XIV 2. 3; De bell. I 6. 2). On the territory of Syria, a Roman province was formed with the center in Antioch; Damascus came under the protectorate of Rome and became part of the Decapolis (Plin. Sen. Natur. hist. 5. 74; Ptolem. Geogr. V 15. 22). Mark Antony gave Damascus to Cleopatra, but after Octavian Augustus' victory over Egypt, Damascus returned to the province of Syria. Since 24 BC, part of the territory of the Itureans (up to Mount Hermon) also belonged to Damascus.

In Damascus, there was a large Jewish community and many synagogues (cf.: Acts 9. 2). Perhaps some Jews were associated with the Essenes, as evidenced by the "Damascus Document" found in the Karaite geniza in Old Cairo, so named because the text does not contain. once mentioned are those who "entered into the New Covenant in the land of Damascus" (CD 6. 19; 8. 21; 19. 34; 20. 12). Since fragments of this monument are also found among Qumran finds (5Q12, 6Q15, etc.), researchers consider it in the context of the history of the Qumran community (for more information, see Qumran).

It was to Damascus that Saul went with a letter from the high priest, in which he was allowed to persecute Christians. However, the Risen Lord appeared to him on the road, as a result of which Saul turned to Christ, becoming the apostle Paul (Acts 9; 22; 26:12-23). The Nabataean king Aretha IV, who defeated Herod Antipas, put his governor at the head of Damascus. An episode from the life of the apostle Paul, described in 2 Corinthians 11:32 and Acts 9:25, belongs to this time, when he had to flee Damascus by climbing down the wall in a basket (he returned to the city later after spending some time in neighboring Arabia - Gal 1:17). The Roman emperor Caligula (37-41) completely handed over Damascus to Aretha, under whose rule it was until the death of the king in 39/40. Josephus reports that in 66, during the First Jewish War, the inhabitants of Damascus killed 10.5 thousand Jews (Ios. Flav. De bell. 2. 20. 2; 7. 8. 7 it is said about 18 thousand, with wives and children).

After the annexation by Rome of the semi-independent Syro-Palestinian principalities at the turn of the I and II centuries A.D., Damascus found itself safe in the imperial possessions. The city enjoyed the special favor of the emperors; in 130, Hadrian granted it the status of a "metropolis", and Alexander Severus - a "colony" (after 222).

The internal peace and order established by Rome led to the rapid flourishing of Damascus and construction activity. Rome. Damascus occupied 115 hectares, had about 35 thousand inhabitants; taking into account the adjacent rural district - 50-60 thousand. In the first century A.D., the city was rebuilt according to a new plan. 4-coal walls (1500×750 m) with 7 gates surrounded the Aramaic, Hellenistic and Nabataean quarters, outlining the space within which Damascus existed almost all the Middle Ages. A citadel was supposedly located in the north-western corner of the defended territory. New canals were dug and an aqueduct was built to supply water to the population. South of the road from the temple to the forum (ex. agora) and parallel to it, the city was crossed by the main street of 25 meters wide (decumanus maximus). The street inherited its configuration from Aramaic times, had several bends, but was called "Straight", which caused ironic remarks in literature, including in the Acts of the Holy Apostles (9.11). The sacred center of the city remained the temple of Zeus-Hadad, which received the Latin name of Jupiter of Damascus. The sanctuary was rebuilt several times in the I-III centuries. The temple stood in the center of a vast courtyard (120×80 m) surrounded by a portico, its fragments have survived to the present day.

Despite the fact that Christians were already in Damascus by the time of the conversion of the Apostle Paul, almost nothing is known about the history of the Christian community of the city in the first centuries A.D. Only in the IV century, with the heyday of the conciliar movement in the Eastern Church, the names of some bishops of Damascus who participated in the Councils of the era of trinitarian and Christological disputes appear. The Byzantine era brought changes to the architecture of Damascus, primarily related to the construction of Christian churches. Subsequently, the Damascus churches were repeatedly destroyed, and none of the existing ones, with the exception of the church of St. Ananias, contains elements of Byzantine structures. The city's main Christian basilica was erected on the site of the temple of Jupiter, apparently in 391, under Emperor Theodosius I. Its layout and dimensions, as well as the original name, are not exactly known. The legend of the burial on its territory of the head of St. John the Baptist (the temple was consecrated in his name) arose after the end of the VI century.

The pagan culture of Damascus has long coexisted alongside the Christian one; Christians made up the majority of the population hardly before the middle of the IV century, and in the rural district even later. Nevertheless, the Bishop of Damascus followed in the hierarchy of the Orthodox Church of Antioch directly after the patriarch. In the era of Christological disputes and church schisms of the V-VI centuries, monophysitism had a strong position in Damascus. Bishop Mammianus, a supporter of Severus of Antioch, was deposed and exiled in 518 for his commitment to monophysitism among many Syrian hierarchs.

In the civil administrative system of the empire, Damascus was the capital of the province of Phoenicia of Lebanon. After 495, the governor's palace was erected on the south-eastern side of the temple fence. In the Byzantine era, the urban layout began to change. The centralized regulation of building, characteristic of Roman times with its commitment to straight lines and distant prospects, has disappeared. Due to the replacement of wheeled vehicles with pack animals, there is no need for wide streets. The rectangular network of straight Roman streets gradually began to be built up chaotically.

In the VI century, the security of Damascus directly depended on the vassal Arab state of the Ghassanids, which covered Southern Syria from the raids of hostile desert tribes. The possessions of the Ghassanids covered Damascus in a semicircle from the east and south. In the 80s of the VI century, there was a conflict between the Byzantine authorities and the Ghassanid elite, allied relations were interrupted. Damascus has once again turned into a border town on the edge of an uncontrolled desert.

In 613, Damascus was captured by the Persians of Khosrow II, who did not cause much damage to the city. Perseid. The garrison stood in Damascus until 628, the following year the city returned to Byzantine rule.

Damascus in the Middle Ages. The Arab conquest.

Epidemics, the Byzantine-Persian wars and the conflict between Orthodoxy and Monophysitism weakened the Byzantine Empire, and it could not offer serious resistance to the Arab invasion of the Middle East in the 30s of the VII century. The army of the commander Khalid ibn al-Walid besieged Damascus in March 635. The population of the city, burdened by the power of Byzantium and not counting on outside help, opened the gates to the Arabs in September. According to the later tradition, negotiations on the surrender of Damascus were conducted by one of the city officials - Mansur, the ancestor of St. John of Damascus. The Muslims guaranteed the inviolability of Christian churches and the property of the inhabitants but were taxed with a poll tax. In the spring of 636, a large Byzantine army launched an offensive against the Arabs, they left Damascus and retreated to Zaiordan. In August 636, in the battle of the Yarmouk River, the Byzantine army was defeated, and soon after that the Arabs finally conquered all of Syria. Damascus was occupied by them for the second time in December 636. Caliph Umar appointed Yazid ibn Abu Sufyan as the ruler of the city, and after his death in 639, his brother Muawiya. In 659, Muawiya has proclaimed caliph and became the founder of the Umayyad dynasty (661-750 years). Having gained the upper hand in a bloody civil war and has established his authority throughout the caliphate, Muawiya made Damascus the capital. During the reign of Muawiyah and his successors in the mid-VII - mid-VIII centuries, Damascus became the political center of the entire Middle East and achieved prosperity.

The number of Muslims living in Damascus was replenished with migrants from the cities of the Hejaz, they occupied the houses of the Greeks who left the city, but nevertheless Christians remained the majority of the population for several centuries after the Arab conquest. Bedouin Arabs, burdened by the urban environment, preferred to settle on the surrounding plains. The residence of Muawiya before his election as caliph was located in the former Ghassanid headquarters of Al-Jabiya, 70 km south of the city. After moving to Damascus, Muawiya settled in a palace rebuilt from the former residence of the Byzantine governor.

The main architectural monument of the Umayyad era was the grand mosque, the center of the religious life of the capital of the Muslim Empire. For the construction of the mosque, the 1500-year-old sacred center of Damascus was used - the territory of a huge courtyard that formerly surrounded the Basilica of St. John the Baptist. The construction of the mosque on this site personified the historical continuity of the former civilizations of Syria. Immediately after the Arab conquest, the Muslims took the south-eastern corner of the temple courtyard under the mosque. In the 2nd half of the 7th century, due to the growing number of adherents of the new religion, the caliphs Muawiya and Abd al-Malik repeatedly offered Damascus Christians to cede the temple but were refused on the basis of guarantees of the inviolability of Christian churches provided by Khalid ibn al-Walid when surrendering the city. However, Caliph al-Walid confiscated the Basilica of St. John and ordered it to be destroyed. The Cathedral of the Damascus Christians became the Church of the Most Holy Theotokos (Arabic al-Maryamiya) on a Straight street, next to the residence of the Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch. A huge Umayyad mosque was built on the site of St. John's Temple. The head of St. John the Baptist, who is also revered by Muslims as the prophet Yahya ibn Zakaria, was kept in a special tomb near the eastern wall of the mosque.

In the 40s of the VIII century, the Umayyad state entered a period of crises and internecine wars. Caliph Mervan II moved his residence to Harran in Northern Mesopotamia in 744. In an effort to bring Syria to submission, he destroyed the walls of its cities, including Damascus.

There are statements in the literature that Monophysites (Jacobites) prevailed among the Damascus Christians of the VII-VIII centuries, which explains the rapid surrender of the city to the Arabs. However, the sources do not confirm a noticeable Jacobite presence in Damascus, but, on the contrary, they contain a lot of information about representatives of the Orthodox community. A native of Umayyad Damascus was the Byzantine church leader St. Andrew of Crete (+ 740). The secretary of the caliphs Muawiya and Abd al-Malik, Sergun ibn Mansur, the father of St. John of Damascus and the de facto head of the Orthodox community of the entire Islamic Caliphate, had influential positions in the state. John of Damascus held the post of secretary of the caliph before his retirement to the monastery. Apparently, the half-brother of John of Damascus, the hymnographer Bishop Cosmas of Mayum and the hagiographer Stefan Savvait (+ 807), who was considered by church tradition to be the nephew of St. John of Damascus, came from Damascus. In the lives of the ascetics of the Judean desert, written by Stefan Savvait and the Damascene Leontius at the turn of the VIII and IX centuries, many natives of Damascus, who asceticism in Palestinian monasteries, are mentioned. The later tradition called the three patriarchs of Antioch of the 2nd half of the IX century - Nicholas, Theodosius and Simeon - natives of Damascus. This city in the VII-IX centuries was one of the main centers of Orthodoxy in the Middle East.

In 750, the Umayyad dynasty was overthrown by the Abbasids. The center of state life of the caliphate shifted to the east, towards Iraq and Iran. Damascus turned into an insignificant provincial city, the inhabitants of which the new dynasty constantly suspected of disloyalty. Several times in the 2nd half of the VIII - 1st half of the IX centuries, Damascus turned out to be the center of rebellions against the new dynasty. During the Abbasid era, there was almost no new construction in the city, Damascus is rarely mentioned in the sources.

The period of the middle of the VIII - beginning of the XII centuries was the time of the greatest decline of Damascus. Its population has significantly decreased. 3 centuries of troubles and anarchy, when none of the residents could feel safe, led to a radical change in urban development. Damascus has split into a number of isolated neighborhoods with a socially homogeneous population. Surrounded by walls and gates, the neighborhoods turned into virtually isolated cities with their mosques, churches, markets, baths, authorities and self-defense units. The process of disintegration of the city was accompanied by religious segregation. Muslims settled compactly in the western half of Damascus, between the Umayyad mosque and the citadel, Jews - in the south-eastern district, Christians - in the north-eastern part, at the gates of Bab Tuma. Some authors see the process of development of the Christian quarter as the marginalization and decline of the Christian community, accompanied by a reduction in its number and the number of churches. There is no exact data on the number and condition of the churches of Damascus in the Middle Ages. It is known that the Cathedral of the Most Holy Theotokos was destroyed several times. In 924, during the period of exacerbation of inter-confessional tensions in the caliphate, a wave of Christian pogroms took place in the Middle East, including the Church of the Most Holy Theotokos, about which the chronicler Eutychius of Alexandria reported that 200 thousand dinars were spent on its decoration at one time. Gold and silver utensils, porcelain dishes were broken, expensive vestments were damaged or stolen. For the second time, the cathedral was destroyed in the spring of 1009 by order of the Egyptian Caliph al-Hakim. Nevertheless, the church was restored, and in 1184 the Arab geographer al-Jubair spoke with admiration about its architecture and paintings.

The collapse of the Islamic Caliphate.

In the IX-X centuries, Damascus was ruled by various local dynasties - the Egyptian Tulunids (869-905), the Ikhshidids (935-969), was repeatedly attacked by the Hamdanids of Northern Syria (40s of the X century) and the Karmats of Arabia (the turn of the IX and X centuries, 970). During the campaign to Syria of the Byzantine emperor John Tzimisces (975), the ruler of Damascus expressed submission to Byzantium. In 976, after the departure of the Byzantines from Syria, Damascus submitted to the Egyptian Fatimids and then remained under their rule for more than 100 years. The population suffered from the excesses of the military garrison recruited from the Maghreb. Collisions with them have been accompanied by fires and destruction more than once. In 1076, the emir of Damascus broke from obedience to the Fatimids and called for the help of the Seljuk Turks. In 1079, Emir Tutush, the brother of the Seljuk sultan, established power over all of Syria. In 1095, after his death, his sons divided the Syrian lands among themselves. Damascus became the domain of Emir Dukak (1095-1104), who had to repel attacks from the Fatimids, Baghdad Seljukids and Crusaders. The real power over Damascus during this period was concentrated in the hands of Tugtegin, the former tutor (atabek) of the emir. After the suppression of the Dukak family, Tugtegin became the sole owner of Damascus and founded the Burid dynasty, which ruled the city until 1154.

In the XII century, the military and political situation of Damascus, which served as a link between Egypt and Muslim Syria, was very difficult. Crusaders from the Kingdom of Jerusalem threatened the agricultural district of Damascus - Hauran and the Bekaa Valley, and in Northern Syria, the Burids had a dangerous rival in the face of the Zengid dynasty, whose possessions were centered in Aleppo. In the confrontation with them, the Burids repeatedly resorted to an alliance with the Crusaders. In 1148, during the 2nd Crusade, the Crusaders tried to capture Damascus by besieging the city. This forced them to ask for help from the Zengids and eventually led to the establishment of the power of the Zengid emir Khaleb Nur ad-Din in Damascus. Under him, Damascus again became the capital of a vast state that covered the whole of Syria. After the death of Nur ad-Din in 1174 and the short struggle of his successor with the former Zengid vassal, the Egyptian Sultan Salah ad-Din, Damascus and Syria came under the rule of Salah ad-Din, the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Uniting the Muslim Middle East, he inflicted a decisive defeat on the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin (1187), captured Jerusalem and repelled the 3rd Crusade. In 1193, the sultan died and was buried in Damascus. Salah al-Din's sons and brother divided his possessions. Although Cairo remained the political center of the Ayyubids, Damascus retained its importance. In the 1st half of the XIII century, it changed hands more than once during the internecine struggle of various branches of the Ayyubids.

Since the XII century, the rapid economic rise of Damascus begins, information about architectural works in the citadel and the construction of mosques appear. To the north and south of the fortified territory of Damascus, the densely built-up suburbs of Al-Ukaiba and Shagur have emerged. The city has become an intellectual center of the Islamic world and Sunni orthodoxy, opposing Fatimid Shiism and Crusaders. It was the Damascus theologians in the 1st decades of the XII century who carried to the masses the idea of universal Muslim solidarity in the face of crusaders and offensive jihad, which Nur ad-Din and Salah ad-Din made their political program. The manifestation of the Sunni revival was the massive construction of religious schools in Damascus madrasahs. The first was founded in 1098; by the end of the XII century, there were 20 of them, a century later - over 80. The number of mosques also grew rapidly: by 1174, over 400 inside and outside the city, although more than half of them did not have a permanent staff of ministers. Mausoleum-tombs of the Zengid and Ayyubid nobility, as well as hospitals-maristans, combined with medical schools, have become an important feature of the architectural appearance of Damascus. After earthquakes and sieges, the walls of the city and the citadel were repeatedly rebuilt.

Mongols and Mamluks.

The political map of the Middle East changed radically in the middle of the XIII century with the appearance of the Mongols. In 1258, after the capture of Baghdad, Mongol troops invaded Syria. As they approached, the last Ayyubid emir of Damascus, al-Malik al-Nasir, fled the city. In February 1260, a Mongol detachment led by the commander of Khan Hulagu, Noyon Kit-Buga, entered Damascus without a fight. Kit-Buga, who belonged to the Nestorian Christian community, patronized local Christians, and they tried to take revenge on Muslims for centuries-old grievances. Among other things, the Umayyad mosque was converted to a Christian church. However, in September 1260, the Egyptian Mamluks defeated the Mongols in the Battle of Ain Jalut and drove them out of Syria. Pogroms of Christians began in Damascus, the Church of the Most Holy Theotokos was destroyed.

After 1260, Damascus became part of the Mamluk Sultanate. Damascus was one of the administrative centers of the state, the second most important after Cairo. The Damascus province was headed by influential Mamluk leaders who repeatedly challenged the sultans and tried to separate from Cairo. This internal political confrontation of the Mamluks was complicated by the periodic attempts of the Mongol Hulaguid dynasty to conquer Syria. During one of these campaigns, in 1300, the Khulaguid Khan Ghazan captured Damascus for a short time. Part of the city was badly destroyed. The capture of the city by Tamerlane in 1401 had even more severe consequences, accompanied by massive destruction, the death of many residents and the sending of skilled artisans to Samarkand. In 1348, between these conquests, Damascus was devastated by a plague epidemic. Sources tell about the joint prayer of Muslims, Christians and Jews in an attempt to avert the "black death" from Damascus. The epidemic has reduced the city's population by 40%.

Despite the political instability in Mamluk Damascus, constant riots and destruction, the urban economy continued to develop. Damascus remained the main market for Hauran grain, as well as the center of complex handicraft industries, in particular the manufacture of weapons. Since the XIV century, trading posts of European merchants have appeared in the city. New markets are being built, suburbs are growing. Most of the architectural monuments of the Mamluk era are located outside the overcrowded center, outside the city walls, among the gardens and canals of the new suburbs. The population of Damascus, together with the suburbs and surrounding estate buildings, as of the XIII century, is estimated by domestic researchers at 40 thousand people, in foreign literature - 80 thousand before the epidemic of the "black death" and 50 thousand after. Since the XIV century, Damascus has been ceding a leading role in Syria to Aleppo, located at the crossroads of trans-Eurasian trade. Historians also talk about the decline in the field of crafts, especially after the invasion of Tamerlane.

The crisis was experienced by the Christian community of the city, which was periodically persecuted by the Mamluk authorities. Under the Ayyubids and Mamluks, Orthodox Christians were increasingly less likely to hold significant positions in the state administration. The cultural activity of local Christians has decreased, although the work of the bookseller of the beginning of the XIII century. Pimen of Damascus is considered one of the pinnacles of calligraphy in the history of the bookishness of the Melkite Patriarchate of Antioch. In 1367, the patriarchs of Antioch moved their throne to Damascus. Since that time, the post of the Metropolitan of Damascus disappears, its functions are transferred to the patriarch. Until the XVII century, an auxiliary post of "metropolitan of the patriarchal cell" was periodically established in the Patriarchate, who was in charge of the affairs of Damascus Christians.

The Ottoman Empire.

In 1516-1517, the Mamluk Sultanate was defeated by the Ottoman Empire. In September 1516, the Ottoman Sultan Selim I entered Damascus. Initially, the city was placed under the control of the Mamluk emir Janberdi al-Ghazali, who defected to the Ottomans. However, in 1520, al-Ghazali rebelled against Istanbul, and after the suppression of this rebellion in Damascus. direct Ottoman rule was established. Over the next century and a half, 133 Turkish pashas were replaced in the city, many of whom, feeling the fragility of their position, tried to quickly enrich themselves by robbing residents. In the XVIII century, when the power of the central administration of the Ottoman Empire weakened, the regional aristocracy - Ayyans - rose in Syria and other outlying lands, many of whose representatives received high posts in the provincial administration. So, in the XVIII century, several people from the feudal clan al-Azm for a long time were at the head of the Damascus pashalik. The palace of Asad Pasha al-Azem (1749), standing to the south of the Umayyad Mosque, is considered one of the decorations of the city.

Ottoman Damascus stood out noticeably against the background of other provincial cities of the empire. It was one of the most important centers of trade between the Middle East and Europe. The city was home to a significant number of European, primarily French entrepreneurs, whose trading partners and intermediaries were often local Christians. Under the Ottomans, many "khans" were built - shopping complexes that combined the features of a market, a warehouse and a hotel for visiting merchants. To no lesser extent, the prosperity of Damascus was promoted by its role in the organization of the Hajj. The city was a gathering place for pilgrims from the European and Asian regions of the Ottoman state traveling to Mecca. The Pasha of Damascus personally led a pilgrimage caravan to Mecca. In Damascus, pilgrims bought food before a long journey through the desert, on the way back they sold goods purchased in Arabia.

From the detailed population and taxable property censuses conducted by the Ottoman authorities since the XVI century, it can be concluded that the number of inhabitants increased from 52 to 57 thousand and in the XVII-XVIII centuries remained approximately at the same level. To the southwest of the medieval city, along the Hajj road, a new Maidan quarter stretched out in a long ribbon. The main monuments of Ottoman architecture - the mosques of Dervishia (1574) and Sinan Pasha (1591) - were built outside the city walls, which emphasizes the further expansion of suburban development and the shift of the center of religious and economic activity.

The Christian community of Damascus in the XVI century increased rapidly, including due to the migration of Christians from the rural area. In the early Ottoman period, Christians made up 12% of the population of Damascus, Jews - 6%. The census of 1569 registered 1021 houses of Christians in the city, which corresponds to 6290 people. In addition to the traditional settlement zone at the gates of Bab Tuma and Bab Sharki in the old city, Christian districts appeared in the Maidan quarter. There were 5 communities in the city: Orthodox, Jacobites (150 families in 1719), Maronites (50 families in 1710), a small number of Armenians and "Franks", i.e. immigrants from Europe. Since the middle of the XVII century, missions of Catholic orders appeared, which managed to convert part of the Orthodox to the union. After 1724, the Uniate Church emerged from the Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch, whose followers adopted the self-designation Melkita. Due to the fact that the Orthodox hierarchy in Damascus had a strong position and enjoyed the support of the Ottoman authorities, supporters of the union migrated from the city to the coastal areas of Syria and the Orthodox remained the predominant group among Damascus Christians.

In the XVII century, there were about 30 priests in the Orthodox community of Damascus, in the XVIII century - 15-17 priests, as well as 3 churches: the Cathedral of the Most Holy Theotokos, the churches of St. Nicholas and Saints Cyprian and Justina. The underground church of St. Ananias between the middle of the XVI and the middle of the XVII centuries was lost by Christians and passed into the possession of Muslims. The patriarchal residence, located next to the cathedral, was completely rebuilt in the late 50s of the XVII century with funds brought by Patriarch Macarius III of Antioch from Russia. Damascus was one of the centers of Arab Orthodox culture, many figures of the "Melkite Renaissance" of the XVII century lived here - Patriarchs Euthymius III, Macarius III, Deacon Paul of Aleppo, etc. In the XVIII century, an example of the high level of the Orthodox culture of Damascus is the chronicle of the priest Mikhail Barik ad-Dimashka (+ after 1782).

The occupation of Syria by the troops of the Egyptian Pasha Muhammad Ali in 1831-1840 was accompanied by large-scale socio-economic reforms, increased contacts with Europe and an end to discrimination against non-Muslim minorities. With the return of Syria to the Sultan's rule in 1840, the policy of strengthening the central government and modernizing society continued, and European economic and cultural influence grew. Under the pressure of the great powers, the Porte equalized the rights of Christians with Muslims. The growing wealth and influence of Christian communities against the background of the ruin of Muslim artisans and merchants, whose products could not compete with the goods of European industry, led to an increase in social and inter-communal tensions in Syria. The bloodiest conflict was the Damascus massacre in July 1860, in which from 2 to 6 thousand Christians of Damascus died and the Christian quarter of the old city was burned down along with all the churches. The Sultan's authorities, seeking to justify themselves in the eyes of Europe, severely punished the perpetrators. The processes of cultural and technical modernization continued: foreign schools were opened in Damascus, streets were expanded for the needs of wheeled transport, a newspaper began to be published (1897), railways connected Damascus with Beirut (1895), Haifa and Medina (1908).

At the beginning of the 20th century, Damascus became one of the centers of emerging Arab nationalism. The Ottoman authorities persecuted the Arab national movement, especially after the outbreak of the First World War. By order of the Turkish governor of Syria, Jemal Pasha, dozens of Arab nationalists were executed in Damascus in May 1916. During the war, the city became the main base of the Turkish army operating in the Sinai direction. Having suffered a final defeat in the autumn of 1918, the tour. The troops left Damascus, and on October 1, British units and their Arab allies, led by Emir Faisal, the son of King Hejaz, entered the city. Faisal tried to create an independent Arab state in Syria, but the Entente powers decided to transfer the country under the mandate of France. In July 1920, French troops, having broken the resistance of the Arabs, occupied Damascus and overthrew the government of Faisal.

The period of the French mandate in Syria was marked by a permanent confrontation between the French authorities and Arab nationalists. In 1925, an uprising began in Syria under the slogans of gaining independence. In October, rebel detachments tried to capture Damascus, and French troops bombed the city, which led to heavy casualties and destruction. At the same time, during the mandate era, Damascus was developing dynamically. In 1929, a city development plan was adopted. New neighborhoods were built to the north and northeast of the old center, and a modern water supply system was created in 1932.

During the Second World War, France recognized the independence of Syria, but the settlement of the conditions for the withdrawal of French troops in 1945 was accompanied by a new surge of tension and the shelling of Damascus by French artillery on May 25, 1945. Soon, however, all foreign troops were withdrawn from Syria and the country gained full independence. Damascus has become the capital of an independent Syrian state.

Modern Damascus is a major economic and cultural center of the Middle East. The Arab Academy of Sciences (established in 1919), the National Library, the Syrian University (since 1923), the National Museum (since 1921) operate in the city. The population of Damascus, which was about 150 thousand in the 70s of the XIX century and over 400 thousand in 1955, currently reaches 4 million people.

Famous Orthodox bishops of Damascus.

Magnus (between 325 and 340), Philip (381), John (431), Theodore (between 445 and 451), John (458), Mammianus (512-518; monophysite), Peter (515), Thomas (519; monophysite), Eustathius (553), Herman (588), Peter (about 734-743), Agapius (813), Nicholas (839), Michael (870 ), Sergius (1033), Michael (XIII century), Joachim (XIV century), George (1576).

Archaeology, architecture, fine arts.

There is practically no material evidence left from the most ancient periods. The archaeological data are mainly from the Hellenistic period and the Roman-Byzantine era. Historical monuments have been preserved in the old town, as well as in the Salikhiya quarter (2 km to the north). The Greek-Macedonian conquerors planned Damascus on the basis of the so-called Hippodamus system, its cells are distinguishable on modern maps. The route of the central street in the west-east direction (decumanus maximus from Rome. times or via recta - Acts 9. 11) also preserved (Souk-et-Taouil), a small Roman arch, now reconstructed (Bab-el-Kanise), partially survived from the architectural frame.

Under the Romans, the city was surrounded by a new wall, only the eastern gates - Bab-Sharki (III century A.D.) were preserved. Next to them is a Christian district, one of the houses of which is glorified as the house of Ananias, one of the first Christians of the city. In its place stood a pagan temple (2 altar stones with a dedicatory inscription have been preserved); an underground vaulted part of a small early Christian church has survived. The gates in the south-eastern corner of the old town of Bab-Kaysan were rebuilt from Roman ones in the XIII-XIV centuries, the towers have preserved chrysanthemums. Christian tradition connects the salvation of the Apostle Paul in a basket through the window of the wall with this gate (2 Cor 11:32, Acts 9:25), in memory of which a small church of the Apostle Paul was built in the inner room of the gate (1939), "what's with the window".

The temple of the Aramaic deity Hadad was rebuilt by the Romans into the temple of Jupiter of Damascus (I century BC, rebuilt again under Septimius Severus (193-211)); a number of Greek inscriptions of civil content were discovered in its ruins (III century). Part of the monumental pediment and columns of the western propylaea of the outer courtyard of the temple has been preserved in the complex of the covered market-gallery Hamidiya (late XIX century). In Christian times, the church was rebuilt into the Basilica of St. John the Baptist; sometimes this reconstruction is attributed to Emperor Theodosius I (379-395), since the altar of the old pagan temple was demolished during his reign. After the Arab conquest, the basilica, like other churches, received the right to protection, as reported by the Greek text on a fragment of a column found in 1909. For about 70 years it remained the main Christian temple of the city, but then Caliph al-Walid (705-715) achieved the construction of the main city mosque in its place.

The Umayyad Mosque, built between 705 and 715 (708-714/7155, according to R. Burns), is the main historical and architectural object of the city and one of the most important monuments of early Islamic architecture. According to legend, tax revenues from Syria were spent on the construction and decoration of the Umayyad mosque for 7 years. It was built on the model of the Prophet Muhammad Mosque complex in Medina by local and Byzantine craftsmen. The prayer hall of the mosque (136×37 m), badly damaged in the fire of 1893, with 3 transverse naves reflects the plan of the previous Roman temple and Christian basilica; most of the columns and naves of the mosque were borrowed from them. At the intersection of the aisles and the transept stands a dome (erected anew after 1893), supported by powerful square pylons. Between the arches of the south nave is a marble building (after 1893), marking the legendary burial place of the head of St. John the Baptist. A rectangular courtyard adjoins the mosque from the north, separated from the urban development by blank walls. From the inside it is surrounded on 3 sides by porticos with 2-tier arcades, from the side of the prayer hall of the mosque there was also once an arcade. The lower tiers of the western and southern walls of the courtyard and the mosque belong to Roman times, the southern 3-private entrance to the courtyard of the Roman temple has been preserved. The southern wall of the mosque is flanked by 2 minarets (1247 and 1488), the 3rd is located in the middle of the northern wall (the lower part of the IX century, the upper part of the end of the XII century). In the north-western part of the courtyard, a small building of the "public treasury" (Kubbat-el-Khazneh or Bayt-el-Khal) of the early Abbasid period (788, according to the Dussault River) is a deaf 8-sided building, resting on a classical entablature on Corinthian columns, strongly deepened into the cultural layer. In the north-eastern part of the courtyard, there is a similar structure dating from the XVIII-XIX centuries.

The mosaics of the Umayyad mosque appeared simultaneously with the construction of the mosque. They were restored several times (late XI, mid-XII, late XIII centuries), were later covered with layers of coatings and remained unknown until the restoration clearance of 1929; a significant part of the mosaics is the fruit of the reconstruction of the 1st half of the 60s of the XX century. Fragments of the general composition have been preserved (walls and arches of porticos, soffits of arches, courtyard facade of the prayer hall) with images of trees, plants, reservoirs, and fantastic architectural structures with columns, arches and domes - palaces and gardens of the Creator awaiting the arrival of the righteous (perhaps an idealized image of Damascus; distant countries and places of pilgrimage). Mosaics retain many features of late Antique painting, their range is greenish-brown with gold. The mosaics of the "public treasury" most likely belong to the XIII-XIV centuries.

In the X-XI centuries, Damascus acquired a typical building for an eastern city: the blocks are separated from each other by walls, infrastructure with a local market and a mosque (synagogue, church) develops inside them, the houses face the street with a blank wall.

In the 2nd half of the XII century, under Atabeg Nur-ad-Din (1154-1174) and Sultan Salah-ad-Din (1174-1193), the main types of structures were formed in Damascus: madrasah (spiritual school) with a mosque and often with the mausoleum of the founder, hamam (bath), maristan (hospital), khan (caravanserai), suk (market in the form of a street gallery). An exemplary building was the Nur-ad-Din maristan (1154, rebuilt in 1283 and in the XVIII century, now the Museum of the History of Arabic Medicine and Science) - with a lobby topped with a cellular dome (mukarnas), and a courtyard with 4 niches-ayvans. The mausoleum of Sultan Beybars (after 1277), decorated with multicolored marble and mosaics depicting trees and buildings on a golden background, imitating the decor of the Umayyad mosque, is located at the Zahiriya Madrasah.

Among the monuments of the Ottoman era, it should be noted the Takiya Suleymaniya mosque complex (1554-1560), built by the Turkish architect Sinan, as well as 2 grandiose construction enterprises of the governor of Damascus. Asad Pasha al-Azema - Khan Asad Pasha (1752), covered with 9 domes (the central one has not been preserved), and the complex of the Azema Palace (1749-1752, now the Museum of Folk Arts and Traditions) with characteristic alternating stripes of dark and light stone and colored inlay; this palace is the most striking work from the pleiad of late Ottoman residential residences preserved in Damascus.

The reconstruction of a part of the city in the European taste began at the end of the XIX century, having received a special scope during the French mandate. In 1926, the general plan of Damascus was drawn up by French architects. The buildings of the 20-30s of the XX century are well preserved, stylistically close to constructivism and Art Deco.

The National Museum in Damascus is one of the richest art and archaeological collections in Asia (founded in 1919, building 1936-1961). Unique materials include materials from Ugarit and Mari, an extensive Palmyra collection (mosaics, a collection of sculptural portraits, reconstruction of the hypogeum of Yarkhai, 108 A.D.), paintings of the prayer house from Dura-Europos. The main entrance to the museum building (1939-1952) is assembled from the surviving fragments of the Umayyad castle Qasr-el-Khair-el-Gharbi (Western Fortified Castle), built in the Syrian Desert under Caliph Hisham (724-743), with elements of Roman-Byzantine and Persian-Mesopotamian architecture.

Gallery of Images "Urban plan Damascus Syria":

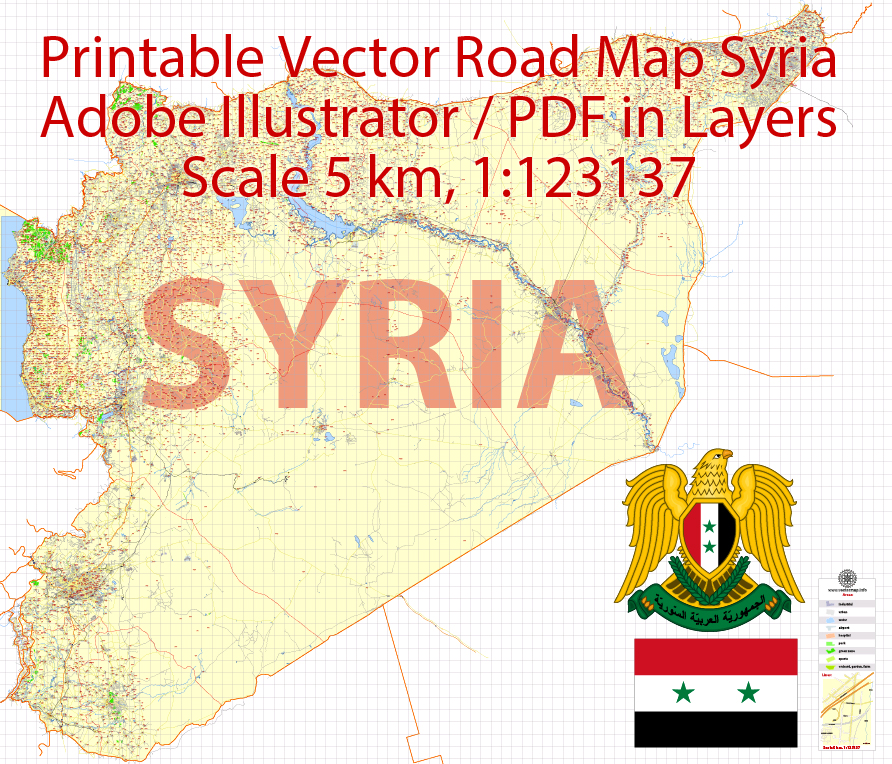

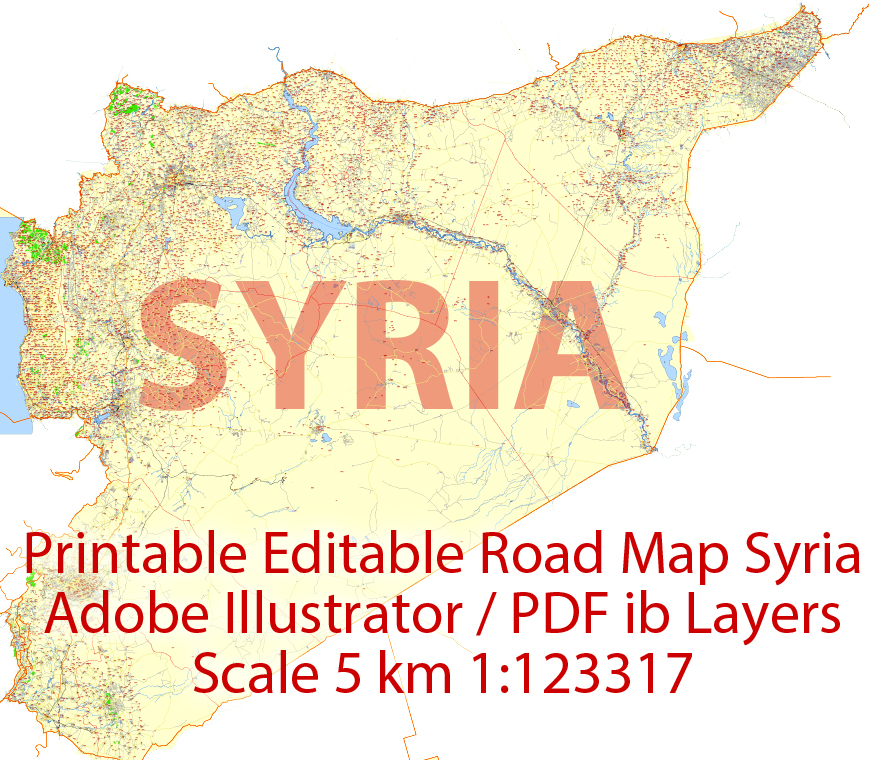

Damascus Syria Editable Maps for Historic Education and Investigation

Printable Vector Maps of Damascus Syriam Fully Editable, in Layers

- Urban plan Hillsboro Oregon

- Urban plan Amiens France

- Urban plan Shanghai China AI ENG LOW

- Urban plan Tallinn Estonia PDF

- Urban plan Las Vegas Nevada PDF

- Urban plan Monaco

- Urban plan full Italy Roads

- Urban plan Dusseldorf Germany pdf

- Urban plan Kharkiv Ukraine

- Urban plan Yuma Arizona PDF

- Urban plan Dortmund Germany ai

- Urban plan Bend Oregon PDF

- Urban plan Donetsk Ukraine

- Urban plan Yale University New Haven Connecticut SVG

- Urban plan Toledo Spain pdf

- Urban plan Bend Oregon

- Urban plan Essen Germany 25

- Urban plan Winnipeg Steinbach Canada

- Urban plan Hobart Tasmania

- Urban plan Bridgeport Connecticut

- Urban plan Fremont California

- Urban plan Moscow low detailed pdf

- Urban plan Miami Florida v309

- Urban plan Havana Cuba

- Urban plan Gdansk Poland PDF

- Urban plan Waterford Ireland pdf

- Urban plan Santo Domingo

- Urban plan Evansville Indiana

- Urban plan Manchester New Hampshire

- Urban plan Colchester UK

- Urban plan British Columbia PDF

- Urban plan Victoria Canada pdf

- Urban plan Thailand Admin Roads

- Urban plan Columbia Jefferson City Missouri

- Urban plan Genoa

- Urban plan Financial District New York City PDF

- Urban plan Allentown Pennsylvania PDF

- Urban plan Novgorod Russia

- Urban plan Belfast Ireland PDF

- Urban plan Massachusetts State

- Urban plan Copenhagen Kobenhavn Denmark pdf

- Urban plan La Porte Baytown Texas ai 15

- Urban plan San Francisco Oakland California CDR

- Urban plan Yale University New Haven Connecticut PDF

- Urban plan Richmond Virginia

- Urban plan Europe Full Extra Detailed CDR

- Urban plan Tel Aviv Israel ai

- Urban plan Greater Miami Florida 4 AI

- Urban plan Belgium Admin

- Urban plan Murmansk Russia

- Urban plan Dublin Ireland ai

- Urban plan Germany Admin Roads PDF

- Urban plan Hamburg PDF

- Urban plan Copenhagen Kobenhavn Denmark low

- Urban plan Mountain View California 13 PDF

- Urban plan Chita Russia

- Urban plan Bern Switzerland

- Urban plan Naples Napoli Italy

- Urban plan Perm

- Urban plan Hillsboro Oregon CDR

- Urban plan Syktyvkar

- Urban plan Sioux City Iova ai

- Urban plan Jerusalem Israel pdf

- Urban plan Prague Praha metro Czech Republic

- Urban plan Columbus Ohio ai

- Urban plan Portland Vancouver pdf

- Urban plan Pakistan Full

- Urban plan Lancaster Pennsylvania PDF

- Urban plan Portland Oregon

- Urban plan Utrecht Netherlands 25

- Urban plan Brunswick Georgia PDF

- Urban plan Paris full Grande France pdf

- Urban plan Melbourne Australia PDF

- Urban plan Lahore Pakistan

- Urban plan San Diego Tijuana California

- Urban plan Vladivostok PDF

- Urban plan Barnstable Massachusetts AI

- Urban plan Greater Miami Florida 4 PDF

- Urban plan Vienna Wien Austria pdf

- Urban plan Travis County Austin Texas

- Urban plan Hartford Connecticut

- Urban plan Denver Metro

- Urban plan Trondheim Norway

- Urban plan San Francisco Oakland

- Urban plan Darwin Australia PDF

- Urban plan Krakow Poland

- Urban plan Czech Republic Roads

- Urban plan Brussels Belgium PDF

- Urban plan Heathrow Feltham Hounslow AI

- Urban plan Tomsk

- Urban plan Spain Admin PDF

- Urban plan Canberra Australia 17

- Urban plan Jakarta Grande Indonesia 13 AI

- Urban plan Shanghai China PDF ENG

- Urban plan Berlin Germany

- Urban plan Graz Austria

- Urban plan Milano Italy

- Urban plan Berlin

- Urban plan Brno Czech Republic ai

- Urban plan South America Topo

- Urban plan Krakow Poland

- Urban plan Wind Point Wisconsin

- Urban plan Yuma Arizona PDF

- Urban plan Menlo Park California 13 PDF

- Urban plan Riga Latvia ai

- Urban plan Pyrenees Relief Roads PDF